Two Millennia

of Impotence Cures

from Impotence: A Cultural History

by Angus McLaren

Herbal, culinary, and pharmaceutical cures

The most extensive catalog of stimulants was provided in the first century by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. The leek, he asserts, “is an aphrodisiac.” The turpentine tree or terebinth “is a gentle aperient and an aphrodisiac.” Garlic “is believed to act as an aphrodisiac, when pounded with fresh coriander and taken in neat wine.” The water of boiled wild asparagus serves the same purpose. “The Cyprian reed, called donax … taken in wine is an aphrodisiac.” The leaves of clematis “eaten with vinegar … act as an aphrodisiac. … Sexual desire is excited by the upper part of the xiphium root given in wine as a draught; also by the plant called cremnos agrios and by ormenos agrios crushed with pearl barley.” [p. 16]

In ancient Greece and Rome, cures for impotence used parts of animal associated with potency. Snakes (since they were popularly believed to rejuvenate themselves), and the genitalia of roosters and goats were consumed. On the forehead of a newborn foal was found a growth called the hippomanes, which, reported Aristotle, was a powerful aphrodisiac. The penis was often likened to the lizard, which leads Pliny to note the powers of a large one known as the skink: “Its muzzle and feet, taken in white wine, are aphrodisiac, especially with the addition of satyrion and rocket seed. … One-drachma lozenge of the compound should be taken in drink.” [p. 18]

In De Animalbus Albertus Magnus, the thirteenth-century friar, provided exotic remedies for impotence: “If a wolf’s penis is roasted in an oven, cut into small pieces, and a small portion of this is chewed, the consumer will experience an immediate yen for sexual intercourse.” Since sparrows were given to frenetic copulation it followed that: “sparrow meat being hot and dry enkindles sexual desire and also induces constipation.” He described the starfish as a violent aphrodisiac that could lead to the ejaculating of blood but could be cured by cooling plants such as lettuce. [p. 40]

The Ladies Physical Directory (1739) declared that absolute impotence was rare. More common was a “languid or faint Capacity” due to a “Deficiency of the Animal Spirits, or their ceasing to flow in such abundance to the particular Muscles, and other Parts administering to Generation.” Such problems could be caused by strains, excesses, self-pollution, and gleets. Other men shed their semen “almost as soon as they entertain any amorous Thoughts.” Still others, given to “fast living” and drink, had infertile or effete semen or a “Want of Animalcula.” All would benefit from the author’s Prolifick Elixir, the Powerful Confect and the Stimulating Balm that promised to “fortify the Nerves, increase the Animal Spirits, restore a juvenile Bloom, and evidently replenish the crispy Fibres of the whole Habit, with a generous Warmth and Moisture.” They would moreover allow men to prolong the embrace and so provide their partners with “prior Endearments and proper Dalliance to raise their Inclination.” [p. 85]

At the end of the eighteenth century Dr. Brodum offered his Nervous Cordial and Botanical Syrup to repair debility and make men ready for the married state. Ebenezer Sibley, like Brodum and other quacks, published testimonials from the supposedly happy consumers of his reanimating “Solar Tincture.” So did Samuel Solomon, who followed Samuel-Auguste Tissot in listing the forms of “debility arising from self-abuse” and offered his Cordial Balm of Gilead for “impotency or seminal weakness.” He advised patients to take the cordial and bathe their testicles in cold water or a mix of vinegar and alcohol. [p. 86]

Solomon’s Cordial Balm of Gilead was a mixture of cardamom, brandy, and cantharides, which supposedly favored the production of semen and removed the flaccidity of the muscles. On analysis Brodum’s Nervous Cordial was revealed to consist of gentian, calumbo, and cardamom. Though such concoctions were unlikely to have fortified the constitution as promised, they probably did little harm. The same was likely true of Dr. Senate’s Steel Lozenges and Balm of Mecca, R. and L. Perry’s Cordial Balm of Syriacum, Blake and Company’s Neurosian Extract, and de Roos’s concentrated Guttae Vitae. [p. 134]

In the nineteenth century, Frederick Hollick condemned the search for a drug that would cure impotence, but concluded by asserting that there was one substance that, in causing warmth, cheerfulness, and leaving no depressive aftereffect, did restore sexual power and desire—cannabis. [p. 138]

Like Hollick, most doctors provided tonics and stimulants, if only to counter their competitors. An 1830 French work recommended ginseng. William Acton prescribed strychnine and phosphoric acid with either syrup of orange-peel or syrup of ginger. Nux vomica (strychnine), yohimbe, and damiana were especially popular. W. Frank Glenn claimed damiana to be the most effective medicine. In cases of complete inability to produce an erection, he employed a combination of phosphide of zinc, damiana, aresenious acide, and cocaine. [pp. 138-9]

On March 27, 1998, Viagra became the first oral medication to be approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to treat erectile dysfunction. Viagra immediately became the fastest selling pharmaceutical in history. Pfizer’s stock went up 150 percent in 1998. Its sale of Viagra topped one billion dollars in 1999 and it enjoyed a profit margin of 90 percent. Pfizer soon had competitors. The year 2003 saw the arrival of Cialis, made by Eli Lilly and Company and Icos, and Levitra, manufactured by Bayer AG and GlaxoSmithKline. [pp. 235-47]

Mechanical and surgical cures

When electrical experiments came into vogue in the eighteenth century, it was soon asserted that electricity and magnetism could also counter flaccidity. Galvanic cures began to be offered in the 1770s by orthodox and quack practitioners. The famous Dr. James Graham touted the dangers of impotence caused by either masturbation or marital excesses, both of which could be cured by cold bathing, moderation, and his amazing electrical bed. [p. 86]

John J. Caldwell described in detail the composition and function of the erectile tissue and how an erection was produced by nervous force. If it was impaired he called for electricity—“either static, dynamic or interrupted”—to stimulate the production of nerve force. Damiana in combination with electricity was used, he claimed, in “many cases of partial loss of virility with marked success.” Hammond explained how galvanism could be applied with electrodes attached to the spine, perineum, testicles and penis, though he described the effect as “rather unpleasant.” To distinguish themselves from quacks, doctors disparaged all belts, disks, and other apparatuses. Nevertheless Vincent Marie Mondat—a distinguished French physician—was credited with the most outlandish of the various external appliances. He invented the “congestor,” a vacuum pump or “exhausting apparatus,” which in drawing blood into the penis was designed to promote erection. [pp. 138-9]

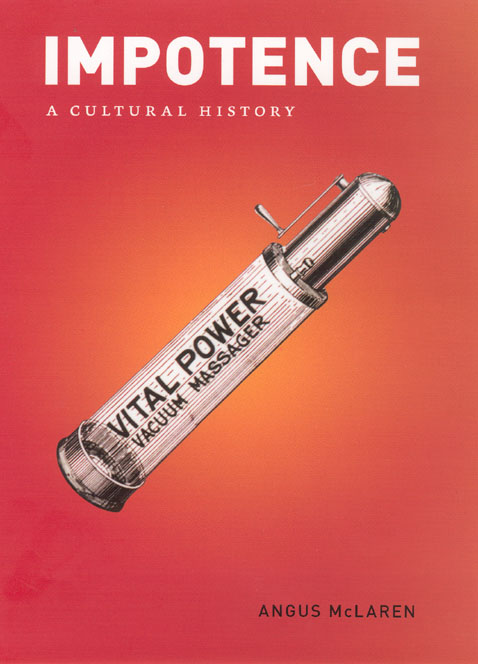

The Vital Power Vacuum Massager. A 1920s advertisement touting the benefits of a tubular device with a crank at the top that supposedly increased blood flow to the penis. [By permission of the National Library of Medicine.] | |

Loewenstein sang the praises of penis supports made of light metal, especially his own Coitus Training Apparatus, a sort of training wheels for the penis. Consisting of two rings for each end of the penis and rubber covered wires in between, the support was covered by a condom before penetration. Though he cautioned that care be taken that the support and the penis went in the same direction, Loewenstein promised that the partner of the “dexterous man” would not know he was using it. He called it a “training” apparatus because he believed that in many cases the erection of the flaccid penis would occur after entry, and once learnt could occur normally. Women were presumably entranced by neither the device nor the care needed to “extricate the apparatus.” [p. 185]

In 1913 Victor Lespinasse, a Northwestern University professor of genitourinary surgery, reported that he had planted slices of human testicle into the muscle of a man who had lost his testicles. Four days after the operation, Lespinasse claimed, the patient had strong erections and insisted on leaving hospital in order to gratify his desires. [p. 186]

The first experiment in grafting an entire testicle was performed by Dr. G. Frank Lydston on himself, on January 16, 1914. Expressing his disappointment that vulgar prejudices heretofore had prevented the exploitation of the sex glands of the dead, Lydston coolly reported how he transplanted into his own scrotum a suicide victim’s testicle. [p. 186]

L. L. Stanley, resident physician of the California state prison in San Quentin, reported in 1922 that he had first implanted testicles from executed convicts and then moved on to inject into his subjects via a dental syringe solutions of goat, ram, boar, and deer testicles. Altogether he made 1000 injections into 656 men. Stanley had been inspired by work of Serge Voronoff, an eminent Russian-born medical scientist working at the Collége de France. Voronoff in 1919 scandalized many by transplanting the testes of chimpanzees into men. He asserted that “marked psychical and sexual excitation” typically resulted, followed by a resurgence of memory, energy and “genital functions.” [pp. 186-7]

Surgeons from the 1970s on implanted silicon rods in the penis of impotent men. In the 1980s American Medical Systems offered three models, the Malleable 600 Penile Prosthesis consisting of two silicon rubber rods that could either be bent for comfort or straightened for penetration, the Dynaflex Penile Prosthesis with two fluid filled cylinders that when squeezed inflated the penis; and the 700 Ultrex Inflatable Penile Prosthesis complete with reservoir and pump hidden in the scrotum. Inflatable penile implants were not initially examined by the Food and Drug Administration and were plagued by failures and infections. Nevertheless it was estimated that within a decade 250,000 to 300,000 had been inserted. [pp. 236-7]

Magical, ritual, and psychological cures

Fourth-century medical man Theodorus Priscianus advised “reading tales of love.” He went on to suggest: “Let the patient be surrounded by beautiful girls or boys; also give him books to read, which stimulate lust and in which love-stories are insinuatingly treated.” [p. 15]

To protect himself against impotence a Roman man might wear a stone talisman or amulet. It was claimed that the “right molar of a small crocodile worn as amulet guarantees erection in men.” In Rome males wore as protection against the evil eye a replica of the penis, called the fascinum from the word to “bewitch.” And finally one could make an appeal to the gods. “While you’re alive I’m hopeful rustic guard / Come. Bless me, stiff Priapus: make me hard.” [p. 19]

Seventeenth-century astrologer-herbalist Nicholas Culpeper and midwife Jane Sharp recommended that a man, who due to magic could not give his wife “due benevolence,” should piss through her wedding ring. In France the man was enjoined to piss or pour white wine either through the wedding ring or through the keyhole of the church in which he had been married. A large painting titled Venus and Cupid by Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480–1556) portrayed one version of this belief in sympathetic magic. [p. 52]

William H. Masters and Virginia E. Johnson, the most important of the sex therapists who in the 1960s, dealt with both nonorgasmic women and impotent men. Their simple message was that, armed with new, scientific knowledge, overcoming marital problems was relatively easy. All that was required was a two week training session costing $2,500. By teaching techniques of orgasmotherapy, starting with an education in masturbation, they claimed it was possible to ignore cultural conditioning and circumvent the psychoanalytic preoccupation with the psyche that might demand years of treatment. They reassured their patients that penis size was not important. Men needed only to relax, knowing that sexual intercourse was simply “a natural physical function.” [pp. 222-3]

Helen Singer Kaplan agreed that it was “surprisingly easy” to cure the 50 percent of the male population that experienced occasional impotence or what she preferred to call erectile dysfunction. Since anxiety was the key problem, she enjoined men to abandon an “over concern for partner” and “be selfish.” [p. 224]

Copyright notice: Excerpted and adpated from Impotence: A Cultural History by Angus McLaren, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Angus McLaren

Impotence: A Cultural History

©2007, 350 pages, 6 halftones, 2 line drawings

Cloth $30.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-50076-8 (ISBN-10: 0-226-50076-4)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Impotence: A Cultural History.

See also:

- The Trials of Masculinity: Policing Sexual Boundaries, 1870-1930 by Angus McLaren

- A Prescription for Murder: The Victorian Serial Killings of Dr. Thomas Neill Cream by Angus McLaren

- Our catalog of gender and sexulaity titles

- Our catalog of history titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog