An excerpt from

My Family & Other Saints

Kirin Narayan

Gods’ Eyes

Even before he left home at fifteen to become enlightened, my brother Rahoul had been making sculptures with gods’ eyes. He bought eyes in many sizes from the God’s Eye Shop in the Bhuleshwar temple bazaar of central Bombay. Back from the sweaty trip to town, he stood in the breezy living room of our seaside home, unfolded packets of searing pink tissue paper, and spilled eyes onto his palm. I raised my chin for a better look. Pitch-black irises gazed up blankly from moist-looking whites, a hint of lifelike pink staining each corner.

“All the better to see you with . . .” chanted Rahoul he turned the eyes on me.

“Don’t!” I objected, pulling back fast.

The largest eyes spanned Rahoul’s palm; he looked down, considering, and the eyes considered him back. The tiniest eyes clustered like shiny seeds in the hollow of his hand. Usually, such unblinking eyes looked out from gods and goddesses in temples or in household pujas. Eyes staring from the creases of my brother’s palm were too weird for me. I was intrigued and also scared.

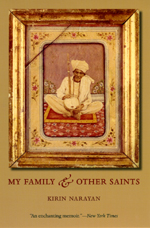

Rahoul-being. Photograph by Stella Snead. | |

Rahoul was my big brother, with a six-year head start on life. Even when he baffled me, I usually assumed I would someday grow into understanding his actions. The gods’ eyes watching from multiple angles in our home reminded me how, since I was the tiniest child, I had yearned for a connection to forces hidden within the visible world. I had examined the frames of mirrors looking for a way through; watched my dolls’ mouths in hopes of conversation; checked on the progress of a fairy chrysalis stuck to the underside of a cane chair before someone else, seeing it as a glob of red Kissan jam, wiped it away. I loved reading partly for the ways that it made the realities around me crumble and grow indistinct; I loved holding a pencil close to the point to write my way into story-worlds. I vaguely understood that Rahoul was reaching for something I couldn’t yet see. Though I frankly preferred art with symmetry, happy colors, and straw-haired heroines, my brothers had all teased me so much for liking The Sound of Music that I now hid my opinions. I listened in and watched everyone else’s reactions to the Rahoul-beings without saying anything myself.

Maw, our mother, was thrilled by the Rahoul-beings. She borrowed one for a Bombay party scene in a Merchant-Ivory film, The Guru, for which she was arranging sets. Our father, Paw, raised his eyebrows, twisted one corner of his mouth, and went back to his room. Our grandmother Ba, who periodically enjoyed personal meetings with gods and goddesses, was at first startled when she came to visit and saw gods’ eyes on a Rahoul-being, but because her adored eldest grandson was responsible, she just laughed. Various guests streaming through our house studied the sculptures, exclaiming over Rahoul’s genius. Even our next-door neighbor, the British surrealist painter-turned-photographer Stella Snead, came across the driveway to take a look.

“They’re rathuh good, aren’t they?” Stella airily pronounced, snorting down her nose with a laugh.

“Remember when he was nine and writing haiku?” Maw asked.

“Don’t, Maw,” said Rahoul.

Stella went back to get her camera and snapped portraits of each being. A few weeks later, I came home from school and found her prints lying out on our living room table. I leafed through them, awed that my teenage brother had inspired a grown-up’s art, especially a grown-up as formidable as Stella. In addition to the series of portraits, Stella had made a black-and-white collage. The Rahoul-beings gathered in a mountainous landscape around a lake, where they all peered, puzzled, over reflections that didn’t quite match.

Later, I wondered: had handling all those gods’ eyes inspired Rahoul to leave home?

: : :

Eyes were, for us, a source of family groupings. For years, grown-up visitors had observed that our Indian-American looks fell into two matched brother-sister pairs. Our sister Maya, the oldest, and brother Deven, the third child, were supposed to look alike because of their hazel “Western” eyes; second-born Rahoul and I, the youngest, were similar because of our darker “Indian” eyes. (Tashi, our adopted brother, who was around Deven’s age, had always looked Tibetan.)

As a teenager, Rahoul’s eyes were still deep-set and intent, fixing on an object as if he could see into it and through it at the same time. Otherwise, he had become unfamiliar, as though viewed in a mirror that stretched and warped his features. He had grown tall, with an oversize head, narrow hunching shoulders, bony elbows, erupting skin, and a nose that the rest of his face had yet to catch up with.

Sometimes, Rahoul brought up our old pairing to torment me.

“Just a few more years and your nose will be just like mine,” he said one afternoon when I appeared by his side to watch him make art. He sat at his desk in the room that had been Maya’s before she left for college. With a Rahoul-being looking on, he experimented with drawing while never lifting his pen from the paper. He bent forward, left elbow jutting awkwardly above his hand, as he outlined figures jumbling, tumbling, and overlapping in big, heaped patterns.

“Never!” I objected. I could never be sure when anyone in the family was making things up to tease me, the gullible youngest. Still, looking at the shiny end of his nose, my hand crept to my face.

“And then your nose will grow even longer. Why do you think we used to call you Baby Elephant?”

I had thought this affectionate title came from a recognition of my special relationship to the royal family of Babar. “That’s not true!” I said.

“You’ll also grow curly hair all over your legs,” Rahoul went on in a matter-of-fact voice. He stuck out a leg, bare below the knee. “Look how hairy my legs are?”

“Don’t!”

“Anyway, you don’t have to worry that no one will marry you, because your horoscope says you’ll have seven husbands.”

“It does not!”

“And you know what? You’ll always be my beautiful baby sister.”

I was not used to being described as pretty, let alone beautiful. Our American grandmother, Nani, had worried within my hearing that I looked too Indian. Maw too always said that my big sister Maya was the beauty, while I was sharp. But there was a big step between having sharp features and becoming a freak! Would I really grow up into some sort of Rahoul-being with an elephant trunk and poodlelike leg hair, surrounded by seven equally weird husbands?

“Don’t tease me!” I ordered.

But Rahoul was smiling so brightly that I couldn’t help smiling too.

Rahoul had reminded me so often of the skills I had learned from him that I could list them inside my own head.

“Hey Baby, I taught you to walk!” he said, and I remembered a faraway time when I had faced him, my hands raised to his, resting my small feet on top of his bigger ones as he walked backward taking me forward, or forward so that I walked backward.

“I taught you to fly!” he said, reminding me how he and Maya had hauled me up by my then-chubby hands to speed along the beach, their feet leaving tracks in the sand but not mine.

“I taught you mirror writing!” he claimed. I immediately pictured Maw’s low dressing room table and Rahoul holding up an EMIT/TIME magazine soon after I’d learned to read. “All spies can read in mirrors,” Rahoul had instructed. “You have to learn how to watch so people never know it.”

I carefully watched my family and everyone coming and going through the house, never entirely sure who I was spying for.

: : :

We lived beside Juhu Beach, in the northern suburbs of Bombay, inside a long, fenced stretch of coconut grove that contained three houses: my parents’ house, our American grandmother Nani’s house, and Stella’s house. The land had been leased to us with the understanding that once or twice a year a swarm of bare-chested, bare-legged men would fling their arms and legs around the trees and climb straight up to harvest smooth green coconuts. Maw had designed the low, whitewashed houses to accommodate the trees. Set into our porches were squares of earth from which coconut trunks rose, through the roof, releasing a fine spray during the monsoon.

Paw remembered childhood outings by ferry to Juhu’s stretches of beach. But by 1959, when our houses were built, Juhu was connected to downtown Bombay by roads and bridges, and Paw could drive to his architecture and engineering office in the old Fort area, almost two hours away. Through the 1960s, Juhu remained partly a fishing village; in the mornings fishermen still brought in their boats laden with flopping silvery nets. Juhu was already becoming famous for people associated with the Hindi film industry. Between our house and the beach stretched a grand mansion rented by the film star Meena Kumari, and saying “behind Meena Kumari” made it easy to direct a taxi from town. On the other side of Stella’s house was the home of a screenwriter named Abrar Alvi; down the road, Kaifi Azmi wrote Urdu poems that were adapted as film songs, and his daughter Shabana would one day be a movie star. Beyond them the actor Prithviraj Kapoor, who we knew as Papaji, had his weekend home and theater.

Paw loved playing with language, and the names he tossed could stick. When he and Maw were poor students with a baby living in a trailer under the Flatiron mountains in Boulder, Colorado, he had called for her, in a hillbilly twang, “Hey Ma-a-aw!”—to which she answered, “Hey Paw!” My big sister Maya picked up these titles and passed them on to the rest of us, born later in India. As the child born last, into family traditions that were already set, I found that having a “Maw” and a “Paw” was awkward to explain when everyone else’s parents were Mummy and Daddy, Mama and Papa, Ma and Baba, or Ammi and Abba. The only other Maw and Paw I’d heard of were in Bob Dylan’s song about Maggie’s farm, and they didn’t seem like the sort of people who lived in Juhu.

Maw often told the story of how I was born because of their move to Bombay from Nasik, where she and Paw had lived with his family for eight years. Her mother, Alice Fish Kinzinger, whom we called Nani, had retired from her job teaching art in Taos, New Mexico and decided to move to Bombay too. She arrived with seventeen steamer trunks and a request: “I haven’t had a chance to enjoy any of the grandchildren. Have another for me.” One of those trunks was filled with clothes for a baby girl; Maw said I was lucky to fit the plan.

Maw, Paw, and kids, 1962. Standing: Maya. Seated, from left,: Deven, Paw, Kirin, Tashi, Maw, Rahoul. Photographer unknown. | |

Nani was my doting, almost constant companion. I had lived with her across the driveway from the main house. She taught me to read and write when I was barely three: first printing, and later the looped script of her childhood schoolhouse in Grand Rapids, Michigan. As I grew bigger, she sewed not just my clothes but also tiny matching outfits for my dolls. But by 1967, Nani could no longer stand the heat, the bugs, the chaos that encircled her daughter’s life. She moved back to New Mexico, taking Maya to college.

With Nani gone, my existence had lost substance. Without her constant protection, something scary happened to me that I didn’t have words for, only fears that would tighten into a banging heart and stinging throat. I ran mysterious fevers and was absent from school so often that when classmates assembled a crossword using our names, the entry for which mine was the clue (six letters, ending in Y) was not “brainy” (as I had hoped) or even “skinny” (as I’d feared) but “sickly.” Sickly! I cringed at the shaky weakness of that word. I often looked away from the thin girl who watched me in the dressing room mirror, her dark eyes rimmed with dark circles. Observing other people was easier than looking too hard into myself. That was one reason I hovered around Rahoul and the many visitors who came through our house.

Weekend party, Juhu, mid-1960s. Photographer unknown. | |

I’d learned early that if grown-ups thought a child was occupied, they would talk as freely as if she wasn’t there. So as grown-ups swapped accounts of events experienced, observed, and imagined, I kept myself busy. I hopped between squares of pale gray stone on the living room floor or knelt over tiny flowers growing in the grass. I stroked the vibrating undersides of cats’ chins, turned pages of books, colored in gowns of princesses, folded origami. My eyes were studiously lowered, but my ears fanned out like a baby elephant’s.

Maw especially loved talking about wildly unconventional, creative, and surprising people, which is probably why she told more stories about Rahoul than about the rest of us. She enjoyed remembering how in 1963, Rahoul had come in from a walk calling, “Hey Maw! Guess what I found on the beach!”

Maw looked up expecting shells or driftwood or maybe even a stray puppy. Instead, she saw two shaggy British beatniks with backpacks. Rahoul gestured backward. “They are poets!” he said. At that point, he was a poet too, writing haiku. To them, he grandly offered, “You can pitch your tent in our garden.”

These poet-beatniks, it turned out, were precursors of the hippies, and again, Rahoul was partly responsible for bringing them to us.

: : :

In 1968, Maw’s friend Marilyn Silverstone received an assignment from a French magazine to cover the hippies finding their way to India. Marilyn was an American photographer for the Magnum agency, and in 1960 she had done a photo essay about Maw called “East-West Wife” for Coronet magazine. Marilyn usually lived in Delhi, but she thought that Maw could help her locate hippies, so she traveled to Bombay, bringing along a British hippie to serve as a decoy. Maw was off in Udaipur for the week, and Paw was away in Nasik. Nani and Maya—who usually stood in as parents—had left for America. So it was Rahoul who received Marilyn and the hippie called Broderick.

Broderick and Rahoul on the beach, Juhu, 1968. Photograph by Didi Contractor. | |

Broderick and Rahoul reasoned that if the beautiful people and freaks in America crowded around Ravi Shankar, hippies in Bombay would be drawn to a free Hindustani music concert. Rahoul phoned up our family friend, the musician Pandit Ram Narayan, who agreed to play his bowed sarangi in our garden. (Though he shared part of Paw’s name and often visited us, Ram Narayan was not a blood relative but a ritual “rakhi brother” of Maw’s.) With the date set, Marilyn and Broderick went downtown to the area around the Salvation Army and American Express, spreading the word of a Happening among any hippies they could find.

Maw was back by the afternoon that hippies began streaming in from the driveway and the back gate. I put down Gulliver’s Travels and came out to observe. Pandit Ram Narayan’s bow drew out shimmering palaces of emotion among the pipal branches, the coconut palms, the white clouds drifting high above. The hippies wore amazing getups: tie-dye, velvet, and crocheted outfits, with bits and pieces of Indian clothes. They sat on cushions and mats spread out over our lawn, rolling their heads to the music and passing around joints. Marilyn wandered among them, focusing her lenses. Rahoul looked on. When the concert was over, servants brought out a big buffet supper. A few hippies asked if they might “crash” for the night—the mats and cushions were spread out, after all—and, still flushed with excitement, Maw agreed.

This was the moment our home became a Groovy Pad. From the Happening onward, young foreigners with lots of untidy hair began appearing at our open doors, asking for Maw on their migrations between Kathmandu and Goa. They camped out on our porch or in the living room for a few nights, a few weeks, sometimes a few months. We hosted American draft dodgers, German stained-glass makers, French women who had traveled overland. Sometimes people showed up who couldn’t even remember who had sent them. One couple had been robbed and assaulted in their Volkswagen bus but had been left with a piece of paper bearing Maw’s name and address; they camped in our backyard, becoming honorary family, and Maw helped them find jobs—teaching art at our school and serving as Hindi movie extras—until they were able to return to America.

“My address is passed all along the hash trail,” Maw observed with satisfaction.

: : :

But it wasn’t just the gods’ eyes and the hippies that lured Rahoul to leave home. I later realized that Rehana Ma, the first mystic I remember meeting, had a role in this too.

We children came to know Rehana Ma in the winter of 1968, when Maw decided to leave Paw and took us all to Delhi. Maw said she could no longer handle Paw’s drinking and our constant worry over money; Delhi, she thought, would be a good place for her to find interior decorating jobs. None of us children wanted to go to Delhi, and Rahoul in particular was furious about being yanked away from working on his sculptures and drawings. But Maw was adamant that we should at least travel as far as Delhi and then decide what to do next.

We had piled into our old gray Ambassador car along with Maw and a driver, taking a rambling route north, with stops to stay with relatives and friends and to visit monuments. In Delhi, we crammed into the various guest rooms of Maw’s friends. But just as Maw was starting to make contacts for possible jobs and schools, she was needed in Bombay. She left us younger children in Rahoul’s care: me, who had just turned nine, Deven, who was thirteen, and Tashi, who was also probably a recent teenager. (No one was sure of Tashi’s exact age. The dentist had said he was probably around five when he joined us, but other details had been lost when the Chinese invaded Tibet and his family fled to India.)

Delhi cold was colder than anything we had known before; the air was smokier, the city flatter and more spread out. Days passed, and I felt as though we had wandered into a dream where everything was both too bright and too faded, and we ourselves had lost our outlines. In the mornings, Rahoul insisted that we dress warmly in sweaters, then took us down to the Yamuna River, where a fringe of wilderness still stretched out beyond new rows of cement houses. He brought along binoculars so we could scan the water for migrating winter birds or half-burned corpses that had floated downstream from cremation grounds. After lunch, we ventured further: to the zoo, where a chimpanzee smoked the lit cigarettes that laughing visitors threw toward him; the National Museum, where Rahoul herded us through echoing galleries; or the bat-scented monuments in Delhi parks, where we clambered up and down narrow stairs. Most often, by late afternoon, we dropped in to visit Maw’s friend Rehana Ma.

“Rehana Ma is a mystic,” Maw had explained before she left for Bombay. “She’s from a famous Muslim family. She lived in Gandhi’s ashram when she was a young woman, and now she’s also a Hindu.”

“What’s a mystic?” I asked. I knew the word “mystery” and was intrigued.

“A person who talks to God,” Maw said.

Rehana Ma lived in a house that also contained an exhibition of objects that Gandhiji had once used. In the big echoing front room, we viewed a spinning wheel that Gandhiji had rotated to make cotton thread, a copy of the Bhagavad Gita he had thumbed through, and his bottle-cap spectacles.

“Anyone who puts on those glasses sees through Gandhiji’s eyes and starts acting nonviolent,” Rahoul announced.

“Really?” I asked, wide-eyed.

“Yeah, right!” said Deven.

Tashi offered to find a way into the case so we could make off with the glasses, but Rahoul shepherded us onward, down the corridor to Rehana Ma’s room.

To me, Rehana Ma was mysterious as an old brick well so deep that it turned the sky into a silver coin. Her room was dim and close, with drawn curtains, closed shutters, and an aromatic smell that might have been oranges, camphor, or cloves. White patches of leukoderma mottled her face. She wore a knit scarf wrapped around her head and knotted under her chin. She seemed to be wearing a sweater and a sari, but it was hard to be sure since a shawl concealed her torso and her legs were hidden under blankets. She was not sick, as far as I could tell, though she never seemed to leave her bed. I wondered if, as a mystic, she needed to stay put so she could enjoy conversations with her favorite god, Krishna. Other families in Delhi, busy with their routines, didn’t really see us, it seemed, but she, staying put in the twilight, saw not just our displaced present, but our past and future.

“Come, child.” Rehana Ma received us one by one from her bed, grasping our hands as we stepped forward. Rahoul said that she could read character from the way your hand draped around hers. I felt her goodwill and acceptance, but still, when we touched, I was careful to keep my mind on good thoughts.

We children settled on chairs and stools around her, Rahoul usually taking the lead in the conversations. I darted looks at the framed picture by her bed, where a blue-skinned, long-haired Krishna looked on. I hoped I might catch his lips in motion.

“You brothers and sisters have karma together,” Rehana Ma said one afternoon, the whites of her eyes glinting in the semidarkness of the room. “This is why you were born sharing the same parents. You all have been connected over many lifetimes, being born as a group again and again. Sometimes you died together. Just one or two lives ago, you were all together in a building when it collapsed.”

She closed her eyes, consulting the inner vision. I imagined the crash of beams, the floor caving in: the shock of an instantaneous ending instead of the slow, draining departure from life as we knew it in Bombay. I felt a pang for the girl who had fallen asleep to the sounds of waves and sea winds; she too seemed to belong in some other life, and I didn’t yet know whether I should mourn her.

Rehana Ma unexpectedly smiled to herself, then opened her eyes and beamed at us.

“Another person in the group hasn’t as yet joined,” she announced, voice filled with gladness. “You will meet up later!”

I sat up straighter. Wasn’t it about time that I stopped being the youngest and had someone with whom I could be the authority for a change: someone I could teach to walk, fly, and read in mirrors? A few years earlier, when I had delicately brought up the possibility of a baby sister, Maw had said sharply, “It’s never going to happen.” But Rehana Ma, I thought, knew more than Maw when it came to the future. The only problem was the verb she used: what did she mean by “meet up”?

Another afternoon, Rahoul said, “Rehana Ma, I need a guru. I’d like to take off for the Himalayas. Places like Hardwar and Rishikesh aren’t that far from here, right?”

Rehana Ma turned her gaze behind her lids. We waited, happily suspended in the peaceful time-outside-of-time of her presence. Then her lids fluttered open. She looked around, finding us. “Why go to Himalayas?” she asked. “First you go back to Bombay.”

My heart turned into a big, pink blossom of hope. So, she had seen that we wouldn’t remain like ghosts at the margins of friends’ families in Delhi. And truly, Maw returned soon after, her voice sounding unnaturally bright and American after her absence. She told us that she had worked things out with Paw. He had agreed to see a psychiatrist and to stop drinking, and we were going home to Juhu.

But already, Rahoul’s plans for leaving home to find a guru had begun to unfold.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 7-20 of My Family and Other Saints by Kirin Narayan, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Kirin Narayan

My Family and Other Saints

©2007, 224 pages, 23 halftones

Cloth $22.50 ISBN: 978-0-226-56820-1 (ISBN-10: 0-226-56820-2))

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for My Family and Other Saints.

See also:

- A catalog of biography and autobiography titles

- A catalog of Asian studies titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects