An excerpt from

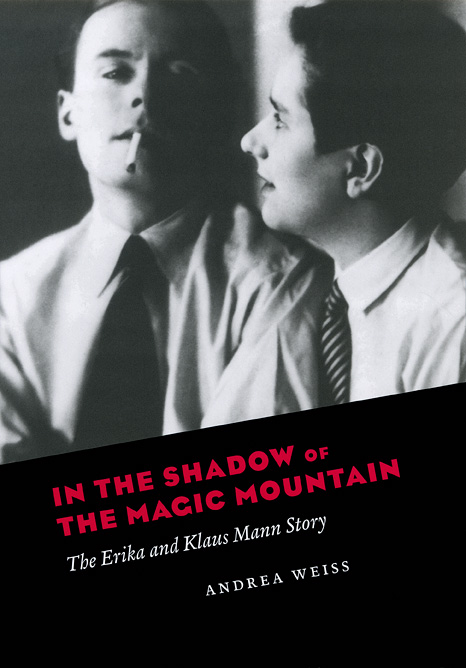

In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain

The Erika and Klaus Mann Story

Andrea Weiss

Chapter 1

Kindertheater

erika: Should the way be this long?

klaus: Oh, every way is long. The death-watch in our chest ticks slowly, and every drop of blood measures its time. Life—a lingering fever. For tired feet every way is too far …

erika: And for tired ears every word too much.

In a large meadow behind an old villa, Erika and Klaus Mann enacted this scene from Georg Büchner’s play Leonce und Lena. Erika, ever dramatic, wore a long white nightgown with a black wool cape thrown over her shoulder, while Klaus pranced about in a black vest, black silk suspender stockings, and short purple bloomers. There was no audience to be found, not even their adoring younger siblings Golo and Monika, although Erika in particular always craved an audience. They reveled in theatricality for its own sake, and did not need to prove their brilliance to anyone. It was the summer of 1922. Klaus and Erika were fifteen and sixteen years old.

“We were six children, and we came in three couples, always one boy and one girl,” is how Elisabeth Mann, their youngest sister, recalled the family constellation. The eldest couple, Erika and Klaus, shared an exclusive make-believe world in which they created a secret language and role-played a variety of bizarre characters. They had little apparent need for their parents, younger siblings, governesses or teachers, all of whom found them enchanting but were baffled by their enigmatic speech, their private jokes and sudden outbursts of laughter.

Erika and Klaus would wander aimlessly for hours around their Herzog Park neighborhood in Munich, or through the woods and meadows of Bad Tölz, a rural Bavarian village where they spent the long lazy summers of their childhood. During these walks they cooked up everything from ambitious theatrical productions to audacious pranks they could try out on the household servants. Often they came across curious strangers, who, mistaking the tomboy Erika for a “little fellow,” would ask them casually about their father, hoping to glean some little piece of gossip about the famous author from his unsuspecting children. The children of Thomas Mann were far too clever to fall for such tricks. Klaus recalled these encounters with righteous indignation:

Why was that stupid old lady so interested in our father? Why did she call him “dad” without even knowing his name? And what on earth made her say that we were “different” and “cute”? … Was it conceivable that people, in their colossal dumbness, found anything to object to in Erika and myself? … We did not need the outside world of the ribald strangers. What could it offer us? It was specious and dreary. In our own realm we found everything we could wish for. We had our own laws and taboos, games and superstitions; our songs and slogans, our arbitrary animosities and predilections. We were self-sufficient.

They were a striking, complementary pair: Erika, tall and imposing with her dark, unruly hair, defiant expression, and scraped knees; Klaus, androgynously beautiful with his shoulder-length blond curls, faraway eyes, and gentle manner. They didn’t particularly look like twins, but they “acted twin-like in an almost provocative way,” according to Klaus. He was fascinated by their mother Katia’s close relationship with her twin brother (who was also named Klaus), and sought to replicate that closeness with Erika. He could have been describing himself and his sister when he imagined this idyllic portrait of his mother and uncle as children:

Hand in hand with her twin brother, Klaus, a young musician, she [Katia] roved through the streets of Munich. Everybody was struck by their peculiar charm… . From their aimless escapades they returned to the familiar palace, their home. There they hid from the vulgar world protected by their wealth and wit, watched and spoiled by servants and instructors. Two bewitched infants who knew and loved each other exclusively… .

Just how much Katia and Klaus Pringsheim loved each other was the subject of public gossip and private distress, especially when Thomas Mann, married to Katia for only a few months, used his wife’s relationship with her brother as the basis for one of his novellas. Blood of the Walsungs centers on a twin brother and sister who share such an intense incestuous bond that even the sister’s fianc is shut out. The Neue Rundschau, which was to feature the story in its January 1906 issue, had already gone to print when Katia’s father learned of it and demanded the story be withdrawn—although whether he, as a Jew whose family converted to Christianity during his childhood, was more disturbed by its explicit incest theme or its virulent anti-Semitism is anyone’s guess.

In acquiescence to his father-in-law, Thomas insisted the printed copies be shredded—his clout as an author was already such that the Neue Rundschau complied—and the story was suppressed for another fifteen years. But the suggestion of incest continued to attach itself to the Mann family. The theme resurfaces in Thomas Mann’s novella Disorder and Early Sorrow (1925) and his novel The Holy Sinner (1951), and it had also appeared in his brother Heinrich Mann’s novel The Hunt for Love (1903), which hints at Heinrich’s fixation on their younger sister Carla. The title characters in Klaus’s play The Siblings (1930), a reworking of Cocteau’s Les enfants terribles, happen to be lovers. Erika and Klaus themselves were dogged intermittently throughout their lives by the accusation that they were “more than siblings.” Although their relationship had an emotionally incestuous dimension, it seems never to have crossed over into the physical realm. Whether that was also true for their mother Katia and her brother Klaus remains an unanswered question.

Born into a rich, highly cultured family at the center of Munich’s artistic and intellectual circles, Katia and Klaus Pringsheim were the youngest of five children. Their father, Alfred Pringsheim, was a temperamental yet highly respected mathematics professor at the University of Munich. He inherited his wealth from his father, a railroad entrepreneur, who converted his Jewish family to Protestantism when Alfred was still a child. Their mother, Hedwig Dohm, was a beautiful and successful actress who gave up the stage when she married the professor and took on the role of prominent society hostess. The Dohm family too had converted from Judaism to Protestantism in the nineteenth century; it was common practice in a country that historically alternated between venerating and despising its Jewish compatriots.

A well-read, intelligent young woman, Katia Pringsheim was afforded an education rare for women in her day. Because girls were not allowed to study at the Gymnasium, a college preparatory high school, she had private tutoring until she was able to pass her Abitur, the qualifying exam for study at university, in 1903. The first female student to enroll in the University of Munich, Katia Pringsheim was also one of the first women in the entire country to pursue a university education. Within the all-male academic community, she delved into the demanding fields of mathematics and experimental physics. After a few semesters, however, her university education and hopes for a professional career were cut short.

Katia Pringsheim was part tomboy and part scholar—not the usual qualities sought in a wife of that era, but qualities which attracted Thomas Mann. He first noticed her getting off a streetcar, math books in hand. Indeed, the entire streetcar noticed her, and not only because she was twenty years old, had sparkling black eyes, an elegant and self-confident style, and strikingly handsome features. The conductor demanded to see her ticket, and to his surprise she refused to comply. She insisted it was not necessary to produce it; she intended to get off at the next stop anyway. With all eyes on her, she called out “Just leave me alone!” and jumped off in defiance. The conductor was not amused, although Thomas was. He determined then and there to meet her.

Thomas hailed from the northern harbor town of Lübeck, where the Mann family had a long and respectable history. He was the second son of a Brazilian actress and a wealthy German senator, who fully expected him to take over the family trading and transport business. Although this position had been held by eldest sons for three generations, it fell to Thomas because his elder brother Heinrich had no intentions of following in their father’s footsteps. Heinrich left Lübeck immediately upon his graduation from school—to pursue his literary ambitions, as well as to get away from what he considered the “stink of prosperity” which permeated his patrician family. Thomas did not endorse this outright rejection of all their father stood for, but he too had doubts about whether he was suited to assume the role of Lübeck’s leading merchant. Hurt deeply by his two errant sons and by the possibility that his glamorous Latin wife was unfaithful, the senator succumbed either to a cancer growing in his bladder (the local doctor operated on him unsuccessfully in the ballroom of the family mansion) or to a poison he took himself; no one ever knew which. The flags in Lübeck were flown at half mast and the contents of his will became the subject of local gossip.

Still a schoolboy when the senator died, Thomas learned that his upright father had a vindictive streak. Executors were instructed to liquidate the company, sell the house and his ship, and give his wife and children no control over the capital. Forced out of the family home, humiliated by the town’s most esteemed citizen, denounced as decadent by the local vicar, the forty-year-old Julia da Silva Bruhns Mann—never fully accepted into provincial Lübeck society on account of her “exoticism” anyway—packed up her three youngest children, Carla, Julia, and Viktor, and moved to an apartment in Munich. Thomas, who had never bothered applying his exceptionally sharp intellect to his studies, left school without completing his Abitur, and joined the family there soon afterward.

In 1901, when he was twenty-six years old, Thomas published his first novel, Buddenbrooks, a thinly veiled fictional account of the Mann family history. His initial impetus was his own personal dilemma; he wanted to tell the relatively short story of how he (just barely) managed to summon up the courage to break with duty and tradition by defying his father’s expectations of him. To do that he first had to establish the family heritage, what he called the “pre-history.” Over a thousand pages later, the book ends before his own particular dilemma ever presents itself. Ironically, the novel endorses continuity rather than dissent: it emphasizes the responsibility of carrying on a family legacy, of being a link in a long chain rather than breaking free.

Buddenbrooks drew so heavily on Thomas’s close observations of real life that it angered the townspeople of Lübeck. Poorly received in its first year, the book had a sudden reversal of fortune when one critic in the Berliner Tageblatt championed it, saying that its reputation will “grow with the years.” Sure enough, decades later the esteemed Swedish Academy singled out Buddenbrooks from the author’s great body of work:

Thomas Mann, recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature for the year 1929, especially on account of his great novel Buddenbrooks, which in the course of the years has found increasingly secure recognition as a contemporary classic.

Katia Pringsheim read Buddenbrooks two years before she met and three years before she married its author. On February 11, 1905, almost exactly one year after he observed her on the streetcar, Thomas Mann and Katia Pringsheim were married at the register’s office on Marienplatz. A small, formal wedding reception followed, held in Katia’s family home, which was one of the finest mansions in Munich. Thomas was eight years older than Katia and dubbed by her four brothers “a liverish cavalry officer” owing to his pale complexion, his dark moustache, and his overly correct bearing.

The only daughter in the family, Katia was escorted to concerts and parties by her four protective brothers with closed ranks—a custom which did not stop once she was married. Perhaps it was the absence of a feminine influence among the siblings, or perhaps it was her feminist grandmother who insisted on equal treatment for her one and only granddaughter, but Katia was fiercely independent, and was merely amused by her brothers’ attempts at chivalry. The streetcar incident and her determination to go to university in an age when virtually no women did reveal a spirited, self-confident, forceful personality, which is how Katia is often described by people who knew her much later in her life. Yet at the age of twenty-one, she capitulated to convention when she gave up her studies to marry Thomas Mann, support his career, and bear his many children. At ninety-one Katia looked back on her past and insisted, “I just wanted to say, I have never in my life been able to do what I would have liked to do.”

For Thomas’s part, the marriage was also a capitulation to convention. He already knew he was homosexual—he had just ended a four-year love affair with a young painter, Paul Ehrenberg. This sexual relationship was a departure from Thomas’s usual pattern of platonic obsession. At fourteen he had become infatuated with an adolescent boy, one of his classmates; this first experience of passionate, unrequited love became an archetype in his later life and in his work. At twenty-five, Thomas no longer saw his homosexual desires as belonging to the caprice of his childhood, although the focus of his sexual passion would continue, throughout his life, to be adolescent boys. Decades later, when he reflected on his relationship with Paul Ehrenberg, he considered it to be the “central emotional experience” of his life. He wrote, “I have lived and loved… . I actually knew happiness, held in my arms someone I really longed for.” At the time, the great joy of that union was tarnished by his self-loathing and disgust at his “abnormality.”

“A punishment he imposed on himself” is what one of Thomas Mann’s biographers called his marriage to Katia, claiming that, “in marrying her he was building a dam to divert the course of his sexual energy, sacrificing his natural inclinations on the altar of his public image.” He broke off with Paul Ehrenberg shortly before his wedding, and it would be more than twenty years before he fell in love with anyone again.

Was it a fear of his own dangerous passions? A need for the public validation that comes with marriage? An insurance policy against the potential life of penury he faced as an author? Whatever his motivation, Thomas Mann, on the rebound from Paul Ehrenberg, was suddenly very determined to marry Katia Pringsheim. First, he had to win over her skeptical father, who was not impressed by the critical success of Buddenbrooks, and who said to his daughter, “A writer isn’t quite the thing, don’t you agree? It’s rather on the frivolous side.” Thomas never grew fond of his future father-in-law, but eventually won the professor’s approval for the marriage by appealing to their shared passion for the music of Richard Wagner.

With the financial support of the Pringsheims, Thomas could embark on a life of heterosexual respectability and material comfort. He genuinely saw the marriage as the socially proper and appropriate step to take, neither dishonorable nor deceitful. If not in love with Katia the way he had been with Paul Ehrenberg, he certainly was captivated by Katia’s cultured background, her family’s position in Munich society, and no doubt the prospect of regaining the privileges of wealth which had eluded him since the death of his father. His own happiness, and hers, did not enter into it.

Heinrich had insisted that a fling with a young girl would quickly cure Thomas of his “nonsense” with Paul Ehrenberg, but marriage to Katia Pringsheim was going too far. He suspected his younger brother of a calculated move for personal gain, something which so infuriated him that he refused to attend the wedding ceremony. Heinrich was more radical and less pragmatic than Thomas ever would be, and, with his penchant for literary caricature and ribaldry, he never achieved anything near Thomas’s stature in the literary world. In fact, Thomas on occasion would have to bail his elder brother out financially. Despite Heinrich’s early success with Professor Unrat (1905; later made into the movie The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich), he never had his heart set on fame, or as Thomas would call it, “greatness,” in the way Thomas had. Even before Buddenbrooks was published, he admitted to Heinrich, “It was always my secret and painful ambition to achieve greatness.”

Wrought with jealousies and competitiveness, Thomas and Heinrich’s relationship as authors and brothers was deeply compassionate, extremely intimate, yet often estranged, and there would never be an easy camaraderie between them. Even as children they had once gone an entire year without speaking, something they would resort to again as adults. Nonetheless, it was Heinrich to whom Thomas first wrote, exactly nine months after the wedding, when Erika was born:

Well, it is a girl: a disappointment for me, I will admit to you, as I had so wished for a son and continue to do so. Why? It’s hard to say. I find a son more full of poetry, more a continuation and new beginning of myself under new circumstances.

Katia had been in labor for forty hours, so one might expect her to be relieved and overjoyed regardless of the child’s sex, but she too was disappointed. All she said about the birth was, “It turned out to be a girl, Erika. I was very annoyed.”

Thomas and Katia got their wish for a son one year later. The boy’s christening as “Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann” sealed his literary fate. The names Klaus and Heinrich represented Katia’s and Thomas’s closest brothers, but together the name Klaus Heinrich is also that of the prince in Royal Highness, the novel Thomas was deep in the middle of writing at the time of his son’s birth. Young Erika kindly chose for her baby brother the less burdensome sobriquet of “Eissi” (the toddler’s mispronunciation of “Klausi”), and henceforth, within the family, Eissi he would remain.

Whether or not his literary forebears had anything to do with it, Klaus seems to have been born a writer. He started writing before he could even hold a pen properly; his earliest pieces he dictated to Erika. No one, not even Klaus, was glad to learn that he had a literary bent. His family tried in vain to discourage him from writing, and he himself referred to it as the family curse. Decades after his death, Erika reflected sadly,

Klaus was a dreamer. Klaus was a poet from the very beginning. And this of course was not at all what my father would have wished for his son. First of all, he knew that any child of his, if he wanted to write, would have a very hard time of it. But for Klaus, writing was as essential as breathing. Without writing Klaus simply couldn’t live.

Thomas Mann’s disappointment at the arrival of Erika and his joy at the arrival of Klaus were false starts—emotions totally at odds with the relationship he would soon forge with each. Klaus would be the source of continual disappointment to him, while Erika was the source of his greatest joy. Despite his initial preference for a son, and his declaration that “a girl is not to be taken seriously,” Thomas’s eldest and youngest daughters, Erika and Elisabeth, became his two obvious favorites, to the chagrin of the others. “When a man has six children, he can’t love them all equally,” would be his defense.

But this was a flimsy excuse for his erratic, often cruel behavior toward the remaining four. Monika, the middle daughter, claimed never to have had an intimate conversation with her father, or even to have had the feeling that she existed for him in his mind. Michael, the youngest son, recalled being beaten with a walking stick and other harsh punishments that prevented him from being able to forgive his father throughout his adult life. He was allowed to listen in on the stories his father read to his sister Elisabeth, but it was made clear that they were not meant for him. And Golo, the middle son, who grew up to become one of Germany’s most prominent essayists and historians, had not one compassionate or affectionate word for his father in his entire autobiography. In the midst of his large family Golo often felt awkward and lonely. Klaus’s callous treatment by his father was by no means unique to him.

Of the six siblings, Erika eventually grew to be the one most devoted to their father. As children, however, Erika and Klaus fixed their devotion on each other, and no one, not their revered parents or their adored younger siblings, could come between them.

Erika and Klaus shared a bedroom, in which they cooked up elaborate schemes, private jokes and tall tales. Together they created a fantasy world of their own making, a “complicated phantasmagoria” as Klaus labeled it, which involved sailors and princesses, voyages and battles—the ordinary stuff of common childhood play, only here the fantasy superseded reality, and the children pitted themselves against the formidable enemy of the outside world.

Sometimes their siblings Golo and Monika—the “middle couple” among the children—were allowed to participate in this secret world if they followed strict orders and didn’t ask questions. And even their parents were occasionally drawn in when the particular fantasy called for it. Their father’s participation was often without his knowledge; his role, although crucial, did not require his presence. At their summer house in Bad Tölz in the Bavarian lake district, the extensive house and gardens became an ocean liner, of which their father, “of course, was the captain, hiding most of the time, in the sanctum of his private cabin.”

In Escape to Life, a book they wrote together in 1939, Erika and Klaus agreed that their youth had been magical, yet they “had enough imagination to be exceedingly naughty and always in hot water.” They loved to tease their younger siblings, and hatch gruesome tales to frighten them. They enjoyed making up stories they would tell each other in public, often mimicking different accents, something Erika could do perfectly. Using a funny Bavarian dialect, Erika would sometimes describe a sadistic child who knifed a poor cow to death. There was no truth in it; they simply enjoyed horrifying their fellow travelers on the streetcar.

In 1913, to accommodate his growing family, Thomas Mann had a villa built at 1 Poschinger Strasse in the Herzog Park district of Munich, right on the banks of the idyllic Isar River. Unlike the previous apartment in Franz-Joseph-Strasse, which had been selected, paid for, and furnished by the Pringsheims, this home, reflecting his growing reputation as an author, he paid for himself (with the help of a mortgage). Three stories high, it held a grand piano, countless books, a large dining room, and Thomas’s study, which led through French windows to a large, beautiful tree-lined garden. Erika and Klaus no longer had to share a room, and neither did Katia and Thomas. In an atmosphere of literary high-mindedness and material opulence, with servants, frequent travels, and distinguished visitors, Erika and Klaus spent their formative years. Klaus claimed that it was as typical a German bourgeois cultured home as one was likely to find.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1-13 of In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story by Andrea Weiss, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Andrea Weiss

In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story

©2008, 310 pages, 36 halftones

Cloth $27.50 ISBN: 978-0-226-88672-5 (ISBN-10: 0-226-88672-7)For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain.

See also:

- Our catalog of literary studies titles

- Our catalog of biography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog