“Miller painstakingly details how a combination of newfound wealth (and a desire to hold on to it), a sudden rise of the middle class (which allowed for a single breadwinner and freed wives to dabble in politics), and the need for new residents to assimilate resulted in a highly conservative political stance riddled with deep-seated racism and 'conspiratorial' John Bircher thinking. Miller’s outstanding research allows him to weave a number of parallel stories, most notably his portrayal of the role of women working behind the scenes to enact this political shift. An insightful examination of a political shift that endures to this day.”–Publishers Weekly

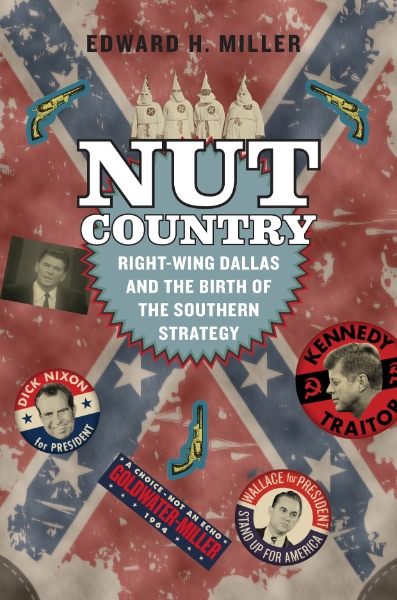

Buy this book: Nut Country

Introduction

President Kennedy’s exploded head was a Mark of the Beast, some said, even during Kennedy’s televised state funeral throughout the long, gray weekend of November 23 to 25, 1963.

On Saturday, an honor guard kept vigil over Kennedy’s body, which lay in state in the East Room of the White House. On Sunday, amid muted drumbeats, a horse-drawn caisson slowly moved the president’s body up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol rotunda. Kneeling beside the casket, the president’s thirty-four-year-old widow kissed the flag draped over her husband’s coffin. A quarter of a million strong—many crying or holding back tears—shuffled by. On Monday, six white horses drew the carriage containing the casket to its final resting place in Arlington National Cemetery. A riderless horse named Black Jack restlessly followed and John F. Kennedy Jr., on his third birthday, saluted his father one last time. President Kennedy’s body lay motionless in the coffin.

But some were convinced it would not be there long: Kennedy was going to rise from the grave and become the Antichrist. Those who believed this tended to be devout premillennial dispensationalists who held that the Bible foretold in detail the chronology of the end of the world, and that the Antichrist’s arrival marks the Rapture, the beginning of the Tribulation, a seven-year period that ends with the final battle of Armageddon. For them, the setting was perfect for the advent of the Antichrist. Via the still new medium of television, the world seemed to be watching, and many heads of state were present in Washington, DC. Many signs suggested that Kennedy was the “beast” described in the book of Revelation. Beyond his head wound, Kennedy had been a member of the Catholic church—the “Whore of Babylon” according to some Protestant readings of Revelation, an institution destined to play a crucial role during the Antichrist’s rule and reign.

Dallas resident H. L. Hunt was one such premillennial dispensationalist, embodying what historian Kim Phillips-Fein has called the “baroque strangeness” of the far right. The richest man in the world by the 1950s, oilman Hunt represented the ultraconservative wing of the Dallas Republican Party. He peddled conspiracy theories, employed apocalyptic rhetoric, and thought in absolutist terms. He was also intransigent in his belief that liberalism was equivalent to Communism. A friend once commented that Hunt “thought that Communism began in this country when the government took over the distribution of mail.” Rejecting ideological compromise of any kind, Hunt demanded absolute victory over a collection of enemies that included not only Communists, fellow travelers, and Democrats but also the Republican Eisenhower administration. The oil tycoon used his fortune to spread his message, parlaying his great wealth into Facts Forum, a veritable media empire that extended into radio, television, and print. Hunt was an eccentric who had nursed at his mother’s breast till age seven. He liked to engage in a type of exercise that he called “creeping.” On the carpet of his office suite, he would crawl like an infant in order to develop what he believed to be a form of higher brain function. He was convinced that he could live forever and believed that he possessed a sixth sense.

On the other end of the Dallas Republican Party from Hunt was Henry Neil Mallon, the quintessential Dallas moderate conservative Republican. Molded by conservatism in his native Ohio, which he left in 1950 to become president of Dresser Industries, Mallon typified the political leanings of his adopted hometown. An active, lifelong member of the GOP, he concentrated on building the party’s institutional structure in Dallas in accordance with his straightforward views: he embraced small government and hailed tax cuts; he assailed Communism and believed in a global Communist conspiracy but rejected as nonsense the idea that high-level American officials colluded with the Kremlin; and he espoused a soft segregationist stance but avoided abject racial demagoguery.

During the early 1950s, Mallon became deeply concerned about Hunt and his burgeoning media empire. In 1953, Mallon wrote about Hunt to his best friend—a Yale classmate, fellow member of the Skull and Bones secret society, and US senator—Prescott Bush, the father of George H. W.

Bush. A “situation is developing here in Dallas,” he wrote, that could “render sterile the Conservative viewpoint.” H. L. Hunt and Facts Forum were setting out to “stigmatize honest dissent, . . . destroy the machinery for objective consideration of honest problems,” and introduce “authoritarianism, absolutism and thought-control.” “This movement,” Mallon wrote, “is no small, localized affair. . . . It is growing daily, in terms of money expended” and “propaganda expounded.”

Mallon saw the need to counterbalance Hunt’s message and, as a result, became more involved in local politics. He established the Dallas Council on World Affairs, a local center-right group that scheduled speakers and discussions. He attended Republican Party events, making generous contributions to moderate conservative Republican candidates and throwing his support behind Barry Goldwater. In his public pronouncements, Mallon advocated the importance of home ownership and lowering tax rates to 25 percent for the most affluent Americans. He shaped the corporate culture at Dresser Industries (which would later become part of Halliburton), hiring many moderate conservative Republicans, including George H. W. Bush, who named his third son, Henry Neil Bush, after Mallon. At Dresser, Mallon created a corporate culture that spoke reverentially of the ability of the free market to allocate wealth efficiently and fairly without government interference.

The example of H. N. Mallon—a Republican stalwart who felt threatened by the rise of ultraconservative Republican activity in Dallas between 1953 and 1963 and was motivated to pursue a brand of relative centrism—illustrates the main argument of Nut Country. This book focuses on relationships and ideological exchanges between the ultraconservative and moderate conservative Republicans of Dallas, Texas, and shows how ultraconservatives like H. L. Hunt, who received widespread national media attention in the 1950s and 1960s, served as important catalysts for the diffusion of conservative ideas across the entire right wing of the American political spectrum. Hunt and other ultraconservatives provided the impetus behind much of the conservative activism of the era, among both moderate and ultraconservative Republicans. They not only pushed moderate conservatives into an increasingly active role in 1950s and 1960s Dallas Republican politics, they also radicalized the right wing of the national party and forced the mainstream to embrace some of their “fringe” ideas.

Ultraconservative Republicans offered moderate conservative Republicans cover in constructing political identities: by labeling ultraconservative doctrines “extremist,” the moderate conservatives could position themselves at the local and national levels as comparatively respectable and credible. Ultraconservatives like Hunt received the lion’s share of the brickbats and catcalls from the American national media. By comparison, more moderate conservative activists, intellectuals, and politicians like H. N. Mallon, Congressman Bruce Alger of Dallas, Senator John Tower of Texas, and Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona often remained shielded from attacks and could develop policies and political styles that mirrored, albeit subtly, those of the “fringe.”

Nut Country shows that ultraconservative Republicans were more essential to the rise of the Right than recent historians have appreciated. Many of the original scholars studying American conservatism acknowledged ultraconservatives but largely dismissed the Right as suffering from status anxiety, burdened by irrationality, possessing a “paranoid style,” or simply reacting to social or political backlash. Beginning in the 1990s, a wave of historians concluded that the committed and persuasive conservative activists of the 1960s and 1970s were not a paranoid group on the wane but mainstream, rational, educated, upwardly mobile “suburban warriors” motivated by ideas gleaned from the books they read. In abandoning a narrative that dismissed and disparaged the Right, scholars made a welcome and salubrious corrective. Yet much as the Right was largely written off in the older scholarship, ultraconservatives and extremists were largely written out of the newer story, with its emphasis on a milder-mannered conservatism. Nut Country highlights ultraconservatives’ decisive role in reconfiguring the American Right at the dawn of the civil rights era. Ultraconservatives here take their place alongside the moderate conservatives—those pragmatic, middle-class professionals and housewives enjoying upward mobility and embodying mainstream values. This book examines the influence of ultraconservative Republicans in Dallas who did not completely jettison their predilections for apocalyptic fantasies, overheated rhetoric, conspiracy theories, and assertions of white supremacy, and argues that these ultraconservatives were even more important than the moderate conservatives.

This book also presents a novel interpretation of the Republican Southern Strategy. As many scholars have shown, Republican leaders like Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan broke the Democratic Party’s hegemony in the Solid South and segments of the North by capitalizing on the reactions of white voters to events of the 1960s, when anxieties about the counterculture, the decline of traditional sexual mores, the decrease in union membership, and the new tendency of whites to see themselves as home owners, taxpayers, and school parents rather than workers, were reshaping their political thinking. Even more crucial, the Democratic Party’s support for affirmative action, school busing, and welfare made these Northern and Southern white voters conclude that the party no longer protected their interests but rather those of African-Americans. In order to attract these disaffected voters into the GOP fold, politicians like Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan developed a Southern Strategy, framing a color-blind discourse of rights, freedom, individualism, and “small government” that appealed to the values of middle-class suburbanites. Republican “color-blind conservatism” predominantly appealed to class advantage, economic rights, “freedom of choice,” and cultural concerns, but race always hovered in the rhetoric. This ostensibly meritocratic discourse secured racial privileges like the spatial segregation of suburbs, and justified a minimum of diversity in public schools. Nut Country, challenging this traditional narrative, argues that the GOP’s Southern Strategy was born not in the 1960s but in the 1950s Southwest, and was in fact explicitly racial in motivation and application. Dallas Republicans were blazing the trail for the GOP Southern Strategy by making racial appeals to white Democrats as early as 1956.

Nut Country reveals the peculiar social and political significance of Dallas by highlighting not only the city’s contribution to the Southern Strategy but its powerful local conservative movement. While historians have written engaging analyses of the postwar conservative movements forged in the metropolitan areas of the Sunbelt, the crescent of states along the southern rim that accounted for much of the nation’s demographic and economic growth in the last half of America’s century, none has fully examined conservative Republicanism in Dallas or Houston. This is surprising, given that none other than Barry Goldwater observed that “there was no better place in the nation to study 1964 from the GOP grassroots level than the state of Texas.” Nut Country places Dallas center-stage in the story of the conservative ascendancy. The city’s geographic position made it the crossroads of the South, West, and Midwest, and its status as a Sunbelt boomtown ensured the arrival of voters from a variety of locations. Dallas was not only a Southern city with a long-standing tradition of white racial supremacist views but also home to many Northern and Midwestern transplants who, while uncomfortable with overt racism, were susceptible to sophisticated encoded appeals to unacknowledged bigotry. The city was thus a perfect test kitchen in which the Republican Party could try out different racial strategies to change its political fortunes. When party leaders in Dallas perfected their dish—through victories such as the landmark election of Republican John Tower to the US Senate in 1961—they could deliver it to the rest of the country. Conservative Dallas Republicans tested spicier versions, but its blander form—a comparatively subtle appeal to white racial superiority—would be served up by the likes of Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan in the years to come.

The story shows how the central religious tenets of Dallas ultraconservative Republicans advanced their secular political ideology. The Republican Party’s original Southern Strategy was partly grounded in a spiritual defense of segregation, which held that the Bible prohibited the integration of blacks and whites. Biblical literalism and premillennial dispensationalism fostered ultraconservative Republicans’ preoccupation with eschatology and spiritual cabals, which they then projected onto the secular world of politics. Many employed apocalyptic rhetoric, purporting that America was always in its death throes. Their embrace of fundamentalism undergirded an absolutist understanding of secular matters, reinforcing their devout belief in the correctness of their opinions and perception of the world as black and white. Their conviction that Satan’s war against Christianity was history’s biggest and longest-standing cabal also likely fed into their preoccupation with conspiracies. For ultraconservative Republicans, history was a grand plot, and conspirators were ubiquitous, omniscient, and omnipotent; random events, when closely scrutinized, were found to fit preconceived patterns that confirmed their conspiratorial worldview.

This tale features characters who were charismatic, prepossessing, uncompromising, and fiercely ambitious, among them General Edwin Walker, who was reprimanded by the Kennedy administration for distributing John Birch Society literature to his troops. After resigning from the US Army, Walker became an ultraconservative icon, establishing his headquarters in Dallas, but ultimately proved unable to handle the pressures of celebrity status. Walker’s latent homosexuality in a place and time that did not openly permit such a lifestyle likely contributed to his downfall. We will meet W. A. Criswell, the powerful pastor of the First Baptist Church of Dallas. In the early 1960s, Criswell defended segregation and doubted that John F. Kennedy, the 1960 Democratic nominee for president, could ever remain free from “church domination.” The cast also includes Edward “Ted” Musgrove Dealey, the publisher of the Dallas Morning News. Under Dealey’s tenure, quipped the retail magnate Stanley Marcus, the News was “opposed to social progress, the United Nations, the Democratic party, federal aid, welfare, and virtually anything except the Dallas Zoo.” As a guest at the White House in 1961, Dealey insulted the president in front of other Texas reporters, calling Kennedy and his administration “weak sisters,” and claimed that the president was “riding Caroline’s tricycle.”

Kennedy’s frustration over Dealey supplies this book’s title, a sharp riposte uttered on the last day of the president’s life. In a Fort Worth, Texas, hotel room on the morning of November 22, 1963, the president’s mood had soured as he read the day’s edition of the Dallas Morning News. “Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas,” read a full-page advertisement placed by three members of the John Birch Society, which went on to claim that the city’s success was due to “conservative economic and business practices,” not “federal handouts,” and to accuse the president of Communist sympathies. “How can people say such things,” Kennedy asked his wife, who was donning a new pink Chanel dress. “We’re heading into nut country today,” he muttered. “You know who’s responsible for that ad? Dealey.”

But Nut Country is not only about outspoken publishers with a penchant for reactionary politics, brilliant if eccentric oilmen, and obstinate preachers with an affinity for the Lost Cause; it is also a story of men and women like J. Erik Jonnson and Margot Perot—the new power brokers of Dallas, the Sunbelt’s new buckle. They were the housewife activists and politicking corporate magnates who mobilized and built the scaffolding of the Dallas GOP. The new power brokers migrated from all parts of the country, but especially the Midwest and Northeast. They came seeking new economic and political opportunities in the free-market environs of Dallas. George Herbert Walker Bush and his family were hardly the only “Lone Star Yankee” immigrants. Jonnson hailed from Brooklyn, New York, moved to Dallas, ascended to the presidency of Texas Instruments in 1953, became active in Republican politics, and was elected mayor of Dallas in 1964. A lifelong Republican originally from Pennsylvania, Margot Perot was the wife of H. Ross Perot, who founded Electronic Data Systems, and a mother to five children. By the 1960s, Margot was not only president of the Valley View Republican Women’s Club but teaching others how to organize precincts and serving as the recording secretary of the Dallas County Council of Republican Women.

These power brokers were a cohort of upwardly mobile, bright, and modern men and women preoccupied with establishing institutional frameworks, raising money for the party, raising children, recruiting quality candidates, and above all, winning elections. They realized that building a successful party organization required eschewing intransigence and absolutism and staking out moderate positions. They drew their economic worldview from the principle that the abundant private interests that sought to influence the free-market system represented a lesser threat to the individual than a hegemonic state.

Bruce Alger, Dallas’s Republican congressman from 1955 through 1965, serves as the window through which much of this story is told. Alger personifies how Dallas’s moderate conservative and ultraconservative Republicans fought for hegemony, forcing public officials to adjust to each new turn in the contest. Born in Dallas in 1918 and raised in the St. Louis suburb of Webster Falls, Missouri, Bruce Alger attended Princeton University on an academic scholarship and flew B-29 long-range bombers during World War II. After the war he returned to Dallas, where by the mid-1950s he had become a successful real estate developer. He was elected in 1954 as the first Republican congressman from Dallas since Reconstruction. Alger was a dashing figure with jet-black hair and tight-fitting dark suits. Many of his contemporaries thought he resembled Gary Cooper, and today he could easily stand in for Mad Men’s Donald Draper. Alger ultimately established a reputation as one of the country’s most reactionary congressmen, though he bounced between the ultraconservative and moderate conservative camps. Historians have largely shrugged off Alger and his attacks on the size of government, his denunciations of Social Security, his condemnations of public housing, and his censures of a federal milk program. In truth, Alger was far more complicated, interesting, and important a figure to the future of the Republican Party than historians have realized.

Most importantly, Alger’s 1956 reelection campaign served as a seminal precedent for the racialization and future Southern Strategy of the Republican Party. It marked the first time that a Southern Republican had abandoned his initial measured stance on desegregation and embraced segregationist positions to maintain and build his electoral coalition. With the ranks of the far right swelling, a moderate stance on integration became politically untenable for Alger. Alger made the baldly political decision to signal to white voters that he was antagonistic toward the interests of civil rights and blacks. His precedent made it unequivocally clear that Dallas Republicans opposed civil rights as well as “handouts” and “special treatment” for African-Americans. Alger’s decision established a powerful precedent that was followed thereafter in a consistent and steady pattern by such Dallas Republicans as Senator John Tower and Dallas County Republican chairmen Maurice Carlson and Peter O’Donnell, as well as 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater.

Nut Country explores the larger development of the modern Republican Party during a profoundly important rebuilding phase, from 1952 to 1964. For the national GOP, these turbulent years of political reconstitution were instrumental in exorcising a great impediment to its future success: its legacy as the party of Radical Reconstruction, of Abraham Lincoln, and of black male suffrage and office-holding. In the mid-1950s, the GOP began the incremental process of breaking from, albeit never completely, its long-standing identification as the party of Lincoln. With Dallas as its progenitor, this newborn GOP evolved into a party that opposed expansion of federal civil rights legislation, and that paved the way for its ascension in the once solidly Democratic South.

While Dallas’s centrality to this story has been overlooked, it is important not to take the implications of this too far. As Geoffrey Kabaservice and Joseph Crespino point out, it is an overstatement to say that the national parties completely swapped positions. Well into the 1960s throughout the South, segregationist Democrats like Georgia governor Lester Maddox and Alabama governor Lurleen Wallace won elections. In a nuanced and exhaustive recent study of race and the Republican Party, historian Timothy Thurber found that in the 1970s “Republicans, especially those in the Senate, proved crucial to fending off attempts by conservatives (usually southerners) in both parties to roll back reforms” crucial to African-Americans. Indeed, although never inspiring the excitement and activism of racially conservative Republicans, moderate and liberal Republicans of the 1960s and 1970s—Everett Dirksen, Nelson Rockefeller, and William Scranton—stood at the forefront of the major civil rights accomplishments of the period.

Moreover, Republicans—with some Dallas Republicans leading the way—altered their political strategies on race in the wake of Goldwater’s loss. The resounding losses of both Senator Goldwater and Congressman Alger in 1964 convinced many Dallas and national Republicans that the old stratagems (appealing to fears of Communism and the loss of property, asserting white supremacy) were no longer effective with enough of the electorate. Some abandoned thinly veiled appeals to racist sentiments, adopting a color-blind language of justice for all in order to widen their electoral reach. While such discourses of tax relief and libertarian economics were sometimes rhetorical strategies couching racial conservatism, many times they were genuine and embodied practical appeals to the newly affluent in the booming Sunbelt. Some Republicans, including Dallas Republicans like Frank Crowley, Peter O’Donnell, and W. A. Criswell, experienced genuine changes of heart on the matter of race throughout the course of the long civil rights era, not only moderating their approach but earnestly reappraising the place of blacks in American society.

And yet, despite the reality of color-blind rhetoric—whether born from genuine conviction or from political calculation—Dallas’s contribution to the racialization of the Republican Party during the seminal period from 1952 to 1964 continues to loom large into the present. The more nuanced, color-blind discourse after 1964 became possible and appeared relatively benign precisely because of the more provocatively racial stratagems that Dallas originated and Goldwater delivered. Blacks were among the first to recognize how much the Republican Party had changed by 1964, and many have neither forgiven nor forgotten it. Barry Goldwater received the same percentage of the black vote in 1964 as Mitt Romney did in 2012: 6 percent. Bob Dylan, the period’s most influential folk singer, could have been speaking to the enduring legacy of the Dallas GOP on race: “the line it is drawn / the curse it is cast.”

Copyright notice: An excerpt from Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy by Edward H. Miller, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)