“In Elephant Don, O’Connell, one of the leading experts on elephant communication and social behavior, takes us inside the little-known world of African male elephants, a world that is steeped in ritual, where bonds are maintained by unexpected tenderness punctuated by violence. It is also the story of O’Connell and the challenges and triumphs of field research. And it comes at a critical time when the slaughter of these intelligent and long lived creatures is at an all time high. The more people learn about them, the more they are likely to help efforts to save them.”–Jane Goodall, founder, the Jane Goodall Institute & UN Messenger of Peace

Kissing of the Ring

Sitting in our research tower at the water hole, I sipped my tea and enjoyed the late morning view. A couple of lappet-faced vultures climbed a nearby thermal in the white sky. A small dust devil of sand, dry brush, and elephant dung whirled around the pan, scattering a flock of guinea fowl in its path. It appeared to be just another day for all the denizens of Mushara water hole—except the elephants. For them, a storm of epic proportions was brewing.

It was the beginning of the 2005 season at my field site in Etosha National Park, Namibia—just after the rainy period, when more elephants would be coming to Mushara in search of water—and I was focused on sorting out the dynamics of the resident male elephant society. I was determined to see if male elephants operated under different rules here than in other environments and how this male society compared to other male societies in general. Among the many questions I wanted to answer was how ranking was determined and maintained and for how long the dominant bull could hold his position at the top of the hierarchy.

While observing eight members of the local boys’ club arrive for a drink, I immediately noticed that something was amiss—these bulls weren’t quite up to their usual friendly antics. There was an undeniable edge to the mood of the group.

The two youngest bulls, Osh and Vincent Van Gogh, kept shifting their weight back and forth from shoulder to shoulder, seemingly looking for reassurance from their mid- and high-ranking elders. Occasionally, one or the other held its trunk tentatively outward—as if to gain comfort from a ritualized trunk-to-mouth greeting.

The elders completely ignored these gestures, offering none of the usual reassurances such as a trunk-to-mouth in return or an ear over a youngster’s head or rear. Instead, everyone kept an eye on Greg, the most dominant member of the group. And for whatever reason, Greg was in a foul temper. He moved as if ants were crawling under his skin.

Like many other animals, elephants form a strict hierarchy to reduce conflict over scarce resources, such as water, food, and mates. In this desert environment, it made sense that these bulls would form a pecking order to reduce the amount of conflict surrounding access to water, particularly the cleanest water.

At Mushara water hole, the best water comes up from the outflow of an artesian well, which is funneled into a cement trough at a particular point. As clean water is more palatable to the elephant and as access to the best drinking spot is driven by dominance, scoring of rank in most cases is made fairly simple—based on the number of times one bull wins a contest with another by usurping his position at the water hole, by forcing him to move to a less desirable position in terms of water quality, or by changing trajectory away from better-quality water through physical contact or visual cues.

Cynthia Moss and her colleagues had figured out a great deal about dominance in matriarchal family groups by. Their long-term studies in Amboseli National Park showed that the top position in the family was passed on to the next oldest and wisest female, rather than to the offspring of the most dominant individual. Females formed extended social networks, with the strongest bonds being found within the family group. Then the network branched out into bond groups, and beyond that into associated groups called clans. Branches of these networks were fluid in nature, with some group members coming together and others spreading out to join more distantly related groups in what had been termed a fission-fusion society.

Not as much research had been done on the social lives males, outside the work by Joyce Poole and her colleagues in the context of musth and one-on-one contests. I wanted to understand how male relationships were structured after leaving their maternal family groups as teens, when much of their adult lives was spent away from their female family. In my previous field seasons at Mushara, I’d noticed that male elephants formed much larger and more consistent groups than had been reported elsewhere and that, in dry years, lone bulls were not as common here than were recorded in other research sites.

Bulls of all ages were remarkably affiliative—or friendly—within associated groups at Mushara. This was particularly true of adolescent bulls, which were always touching each other and often maintained body contact for long periods. And it was common to see a gathering of elephant bulls arrive together in one long dusty line of gray boulders that rose from the tree line and slowly morphed into elephants. Most often, they’d leave in a similar manner—just as the family groups of females did.

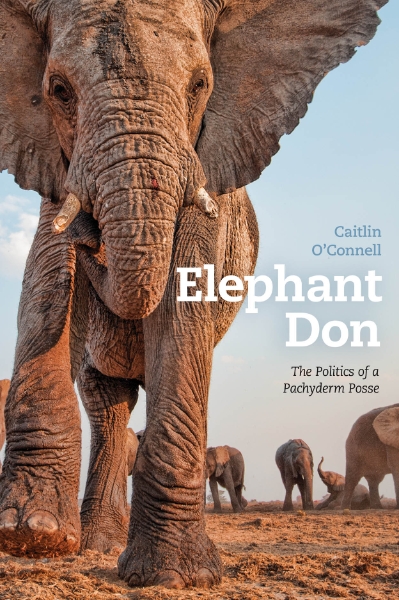

The dominant bull, Greg, most often at the head of the line, is distinguishable by the two square-shaped notches out of the lower portion of his left ear. But there is something deeper that differentiates him, something that exhibits his character and makes him visible from a long way off. This guy has the confidence of royalty—the way he holds his head, his casual swagger: he is made of kingly stuff. And it is clear that the others acknowledge his royal rank as his position is reinforced every time he struts up to the water hole to drink.

Without fail, when Greg approaches, the other bulls slowly back away, allowing him access to the best, purest water at the head of the trough—the score having been settled at some earlier period, as this deference is triggered without challenge or contest almost every time. The head of the trough is equivalent to the end of the table and is clearly reserved for the top-ranking elephant—the one I can’t help but refer to as the don since his subordinates line up to place their trunks in his mouth as if kissing a Mafioso don’s ring.

As I watched Greg settle in to drink, each bull approached in turn with trunk outstretched, quivering in trepidation, dipping the tip into Greg’s mouth. It was clearly an act of great intent, a symbolic gesture of respect for the highest-ranking male. After performing the ritual, the lesser bulls seemed to relax their shoulder as they shifted to a lower-ranking position within the elephantine equivalent of a social club. Each bull paid their respects and then retreated. It was an event that never failed to impress me—one of those reminders in life that maybe humans are not as special in our social complexity as we sometimes like to think—or at least that other animals may be equally complex. This male culture was steeped in ritual.

Greg takes on Kevin. Both bulls face each other squarely, with ears held out. Greg’s ear cutout pattern in the left ear make him very recognizable

But today, no amount of ritual would placate the don. Greg was clearly agitated. He was shifting his weight from one front foot to the other in jerky movements and spinning his head around to watch his back, as if someone had tapped him on the shoulder in a bar, trying to pick a fight.

The midranking bulls were in a state of upheaval in the presence of their pissed-off don. Each seemed to be demonstrating good relations with key higher-ranking individuals through body contact. Osh leaned against Torn Trunk on his one side, and Dave leaned in from the other, placing his trunk in Torn Trunk’s mouth. The most sought-after connection was with Greg himself, of course, who normally allowed lower-ranking individuals like Tim to drink at the dominant position with him.

Greg, however, was in no mood for the brotherly “back slapping” that ordinarily took place. Tim, as a result, didn’t display the confidence that he generally had in Greg’s presence. He stood cowering at the lowest-ranking position at the trough, sucking his trunk, as if uncertain of how to negotiate his place in the hierarchy without the protection of the don.

Finally, the explanation for all of the chaos strode in on four legs. It was Kevin, the third-ranking bull. His wide-splayed tusks, perfect ears, and bald tail made him easy to identify. And he exhibited the telltale sign of musth, as urine was dribbling from his penis sheath. With shoulders high and head up, he was ready to take Greg on.

A bull entering the hormonal state of musth was supposed to experience a kind of “Popeye effect” that trumped established dominance patterns—even the alpha male wouldn’t risk challenging a bull elephant with the testosterone equivalent of a can of spinach on board. In fact, there are reports of musth bulls having on the order of twenty times the normal amount of testosterone circulating in their blood. That’s a lot of spinach.

Musth manifests itself in a suite of exaggerated aggressive displays, including curling the trunk across the brow with ears waving—presumably to facilitate the wafting of a musthy secretion from glands in the temporal region—all the while dribbling urine. The message is the elephant equivalent of “don’t even think about messing with me ’cause I’m so crazy-mad that I’ll tear your frickin’ head off”—a kind of Dennis Hopper approach to negotiating space.

Musth—a Hindi word derived from the Persian and Urdu word “mast,” meaning intoxicated—was first noted in the Asian elephant. In Sufi philosophy, a mast (pronounced “must”) was someone so overcome with love for God that in their ecstasy they appeared to be disoriented. The testosterone-heightened state of musth is similar to the phenomenon of rutting in antelopes, in which all adult males compete for access to females under the influence of a similar surge of testosterone that lasts throughout a discrete season. During the rutting season, roaring red deer and bugling elk, for example, aggressively fight off other males in rut and do their best to corral and defend their harems in order to mate with as many does as possible.

The curious thing about elephants, however, is that only a few bulls go into musth at any one time throughout the year. This means that there is no discrete season when all bulls are simultaneously vying for mates. The prevailing theory is that this staggering of bulls entering musth allows lower-ranking males to gain a temporary competitive advantage over others of higher rank by becoming so acutely agitated that dominant bulls wouldn’t want to contend with such a challenge, even in the presence of an estrus female who is ready to mate. This serves to spread the wealth in terms of gene pool variation, in that the dominant bull won’t then be the only father in the region.

Given what was known about musth, I fully expected Greg to get the daylights beaten out of him. Everything I had read suggested that when a top-ranking bull went up against a rival that was in musth, the rival would win.

What makes the stakes especially high for elephant bulls is the fact that estrus is so infrequent among elephant cows. Since gestation lasts twenty-two months, and calves are only weaned after two years, estrus cycles are spaced at least four and as many as six years apart. Because of this unusually long interval, relatively few female elephants are ovulating in any one season. The competition for access to cows is stiffer than in most other mammalian societies, where almost all mature females would be available to mate in any one year. To complicate matters, sexually mature bulls don’t live within matriarchal family groups and elephants range widely in search of water and forage, so finding an estrus female is that much more of a challenge for a bull.

Long-term studies in Amboseli indicated that the more dominant bulls still had an advantage, in that they tended to come into musth when more females were likely to be in estrus. Moreover, these bulls were able to maintain their musth period for a longer time than the younger, less dominant bulls. Although estrus was not supposed to be synchronous in females, more females tended to come into estrus at the end of the wet season, with babies appearing toward the middle of the wet season, twenty-two months later. So being in musth in this prime period was clearly an advantage.

Even if Greg enjoyed the luxury of being in musth during the peak of estrus females, this was not his season. According to the prevailing theory, and in this situation, Greg would back down to Kevin.

As Kevin sauntered up to the water hole, the rest of the bulls backed away like a crowd avoiding a street fight. Except for Greg. Not only did Greg not back down, he marched clear around the pan with his head held to its fullest height, back arched, heading straight for Kevin. Even more surprising, when Kevin saw Greg approach him with this aggressive posture, he immediately started to back up.

Backing up is rarely a graceful procedure for any animal, and I had certainly never seen an elephant back up so sure-footedly. But there was Kevin, keeping his same even and wide gait, only in the reverse direction—like a four-legged Michael Jackson doing the moon walk. He walked backward with such purpose and poise that I couldn’t help but feel that I was watching a videotape playing in reverse—that Nordic-track style gait, fluidly moving in the opposite direction, first the legs on the one side, then on the other, always hind foot first.

Greg stepped up his game a notch as Kevin readied himself in his now fifty-yard retreat, squaring off to face his assailant head on. Greg puffed up like a bruiser and picked up his pace, kicking dust in all directions. Just before reaching Kevin, Greg lifted his head even higher and made a full frontal attack, lunging at the offending beast, thrusting his head forward, ready to come to blows.

In another instant, two mighty heads collided in a dusty clash. Tusks met in an explosive crack, with trunks tucked under bellies to stay clear of the collisions. Greg’s ears were pinched in the horizontal position—an extremely aggressive posture. And using the full weight of his body, he raised his head again and slammed at Kevin with his broken tusks. Dust flew as the musth bull now went in full backward retreat.

Amazingly, this third-ranking bull, doped up with the elephant equivalent of PCP, was getting his hide kicked. That wasn’t supposed to happen.

At first, it looked as if it would be over without much of a fight. Then, Kevin made his move and went from retreat to confrontation and approached Greg, holding his head high. With heads now aligned and only inches apart, the two bulls locked eyes and squared up again, muscles tense. It was like watching two cowboys face off in a western.

There were a lot of false starts, mock charges from inches away, and all manner of insults cast through stiff trunks and arched backs. For a while, these two seemed equally matched, and the fight turned into a stalemate.

But after holding his own for half an hour, Kevin’s strength, or confidence, visibly waned—a change that did not go unnoticed by Greg, who took full advantage of the situation. Aggressively dragging his trunk on the ground as he stomped forward, Greg continued to threaten Kevin with body language until finally the lesser bull was able to put a man-made structure between them, a cement bunker that we used for ground-level observations. Now, the two cowboys seemed more like sumo wrestlers, feet stamping in a sideways dance, thrusting their jaws out at each other in threat.

The two bulls faced each other over the cement bunker and postured back and forth, Greg tossing his trunk across the three-meter divide in frustration, until he was at last able to break the standoff, getting Kevin out in the open again. Without the obstacle between them, Kevin couldn’t turn sideways to retreat, as that would have left his body vulnerable to Greg’s formidable tusks. He eventually walked backward until he was driven out of the clearing, defeated.

In less than an hour, Greg, the dominant bull displaced a high-ranking bull in musth. Kevin’s hormonal state not only failed to intimidate Greg but in fact just the opposite occurred: Kevin’s state appeared to fuel Greg into a fit of violence. Greg would not tolerate a usurpation of his power.

Did Greg have a superpower that somehow trumped musth? Or could he only achieve this feat as the most dominant individual within his bonded band of brothers? Perhaps paying respects to the don was a little more expensive than a kiss of the ring.

Copyright notice: An excerpt from Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse by Caitlin O'Connell, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)