“This highly original, absorbing, and beautifully written work rethinks Ruskin by anchoring his thought, and that of his friends and associates, in their daily routines, showing how a style of thought we might call “ecological” emerged through prosaic practices. But it also shows the difficulties inherent in creating such a style of thought, and the complexities and compromises that emerged alongside ecological thinking. The issues raised in this book, vital today, will become only more significant in the future.”–Christopher Otter, Ohio State University

Introduction

Sometime in 1883, a London barrister on holiday in England’s Lake District entered a small cottage and sat down beside a dilapidated old spinning wheel. Such wheels had fallen out of use with the invention of steam spinning. The middle-aged bachelor was visiting an eighty-six-year-old local woman to learn how to spin. In a charming account of his struggles at the wheel, he complained, “Everything went wrong: the wheel reversed, the thread broke, and the flax twisted itself up into inconceivable bewilderments.” Despite these frustrations, he persevered. Soon, with the aid of his housekeeper, he began to teach his hard-won new skills to older local women who could barely remember their grandmothers spinning. In time the barrister, Albert Fleming, became widely known for his rural, community-oriented activities. He reached out to dozens of local women and found one of the few remaining men who knew how to work a hand loom. Together, they began to turn hand-spun yarn and thread into handwoven linens. Contrary to the cynical predictions of Fleming’s London friends, they found they were able to sell their rustic creations for a small, steady profit.

This was deeply gratifying to Fleming. He was appalled that these ancient arts had been eclipsed so rapidly by mechanization. He reflected on the booming industrial world with a bitter cost-benefit analysis: “For ‘the virgin labor of her shuttle,’” he wrote, “you shall have cheap Manchester goods; for the sweet singing of poets under blue skies you shall have the roar of ten thousand spindles under black ones.” As he saw it, thoughtless consumption had darkened the skies as well as the soul. Spinning had been a stable and satisfying form of work in the Lake District before it was supplanted by steam-powered machines that debased the lives of workers and consumers alike, warping desires and destroying landscapes. No wonder then that Fleming found pleasure in teaching local women skilled handwork. This seemingly innocuous, eccentric community industry was in fact the fruit of a revolutionary perspective. With his band of elderly ladies and his humble cottage factory, Fleming hoped to counter the forward march of mechanized labor. In doing so, he was heeding the writings of the famous art historian and social critic John Ruskin by combining beauty and skilled craftsmanship with joy in work while maintaining an awareness of nature’s fragility. In this, Fleming and other followers of Ruskin were attempting to revive and preserve a traditional economy that they associated with a better, simpler way of life.

There could be little doubt about the difficulty of the challenge. Every workday in Victorian Britain, hundreds of thousands of workers were streaming into factories to churn out cheap and often shoddily made furniture, cookware, clothing, and trinkets. Even books were mass produced. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the printing of books had been transformed from a painstaking process of hand printing into a dizzyingly rapid process that made full use of new machinery. Publishing houses rumbled with steam-powered rotary printing presses. The buildings where these presses whirled without cease bore some resemblance to a train station, with wheels spinning, pipes gasping, and pistons chugging. The first steam-powered press had been around for a long time, having been bought by the Times in 1814. Most paper in Britain was made by machine by 1830; later innovations included a typecasting machine in 1838, the Wicks rotary caster in 1881, and Linotype machines in 1886. A huge variety of works were constantly coming on the market, including Tennyson’s Tiresias and Other Poems, 1885 (15,771 copies in one year), Charles Darwin’s The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, 1881 (8,500 over three years), Sir John Seeley’s The Expansion of England, 1883 (80,000 in two years), and Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery, 1888 (145,000 in ten years). Such large-scale production offered great hope for the future. New technologies had helped make books and daily newspapers widely available, increasing literacy among the general public. This avalanche of books would seem to have been an unqualified boon for democracy in every sense, helping ease the divide between rich and poor, between the ruling political class and the laborers who could now follow activities in Parliament.

Yet in general, mechanized industries inspired a great deal of ambivalence in Ruskin and his circle of friends and followers. Rapid steam-powered production entailed certain obvious social costs. Skilled handwork was cast aside in favor of dangerous, rattling machines operated by anonymous men and women. Middle-class consumers purchased kettles and footstools with little knowledge of how these items were made. Textile factories in the 1870s roared with deafening machines; spinning belts at times snared women’s hair, scalping them. Children were employed to clear textile waste and fiber dust, sometimes falling victim to the machines themselves. Efficiency had become the guiding principle, with great rewards for those who financed and managed the process even as workers suffered. Although the British Parliament sought to curb the worst abuses with factory legislation, new laws were difficult to enforce, leaving many laborers vulnerable to broken machinery, pulmonary disease from dust, cancer from contact with chemicals, deafness from long days in noisy workshops, low wages, and oppressive management. The London Matchgirls Strike of 1888 drew attention to scandalous working conditions in which white phosphorous used for matchstick production caused toothaches, tooth loss, and finally decay of the jawbone. Nor did having work assure anyone of decent living conditions. Housing reformers highlighted the plight of urban slum dwellers, with lurid accounts of gambling, alcoholism, prostitution, and incest in an underworld of filth and despair. In 1885 the journalist W. T. Stead exposed London’s child prostitution rings, stunning bourgeois readers who had never set foot in the East End. The darkness of industrial England extended also to the atmosphere. Sooty coal smoke from the factory districts obscured the skies and blighted vegetation.

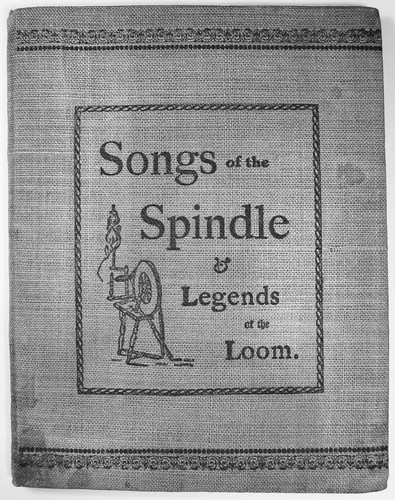

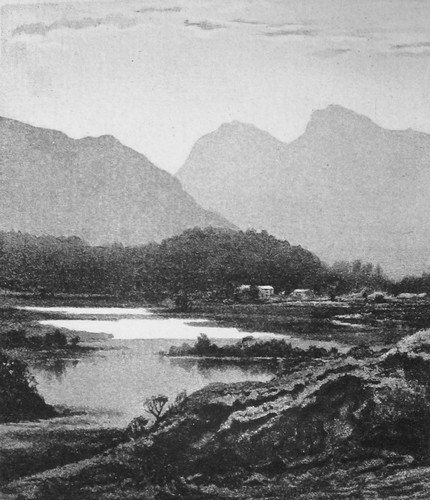

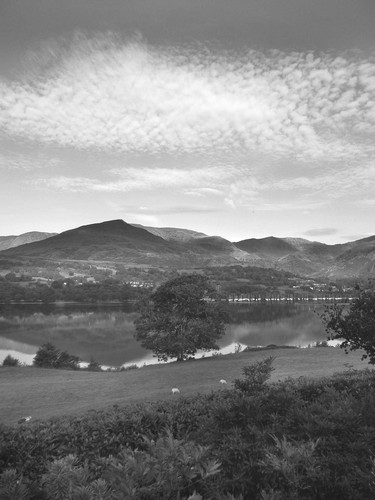

In the face of so many social ills, critics like Ruskin and Fleming despaired of regulating and reforming the industrial city from the inside. Instead, they withdrew to the countryside in search of a new social order and a more thoughtful approach to the use of nature. A slim book from 1889, Songs of the Spindle & Legends of the Loom, opens the door to their alternative economy. A copy of the book survives in the Huntington Library. This modest artifact from Fleming’s linen industry presents a concrete example of an experiment in handicraft production that recalled the earliest days of book and cloth making. At over 125 years of age, it is not at first sight an enchanting creation. The dingy beige cloth cover stretches tautly over its sturdy frame and tends toward burlap in texture. The title, the image of a spinning wheel, a partial border, and a flax plant appear in dull cornflower blue paint on the front and back covers. It is a bit worn and the paint is smudged, but clearly the book is intended to call to mind the natural elements of its making; the preface even tells us the linen cover is “unbleached,” the “colour of the dried flax,” and “the product of hand-work alone.” Most pages are well preserved. The crisp, elegant type setting on hand-cut paper suggests thoughtful, high-quality craftsmanship. There are dozens of poems and illustrations, all relating to the theme of hand spinning and weaving, each with the poet’s or artist’s name beneath it. The first image shows the Langdale Valley in the English Lake District, where the book was made. It is unabashedly picturesque, with undulating fields stretching back toward a modest mountain range. One can imagine in full color the bending gravel roads thick with ferns, the purple heathered hills, and the glassy stream. This image, like everything else about our story, is an invitation to enter the world of its making.

figure 0.1 A handmade book: H. H. Warner’s Songs of the Spindle & Legends of the Loom, 1889.

The dream of this handmade book began when Fleming moved to the Lake District in 1883. He was drawn to the area by a keen desire to be closer to Ruskin, by then a renowned critic of liberal economic thought, well known for his scathing denunciations of mechanized labor and industrial pollution. Ruskin was also the famed author of the five-volume work of art history Modern Painters and a key figure for both the Pre-Raphaelite painters and the Arts and Crafts movement. From his first important publication in 1843 until his death at the turn of the century, Ruskin was a major force in Victorian intellectual and cultural life, so highly regarded and influential that he was offered a final resting place in Westminster Abbey (his family declined the privilege since he had already requested a humble burial plot in the Lake District). Fleming’s house, known as Neaum Crag, sat in the hills just a few miles from Ruskin’s own villa, Brantwood, in Coniston. It thrilled and inspired him to be so close to a much-admired thinker, and soon he was attempting to put Ruskin’s theories into practice.

figure 0.2 Auto-gravura showing the Langdale Valley, from Songs of the Spindle & Legends of the Loom.

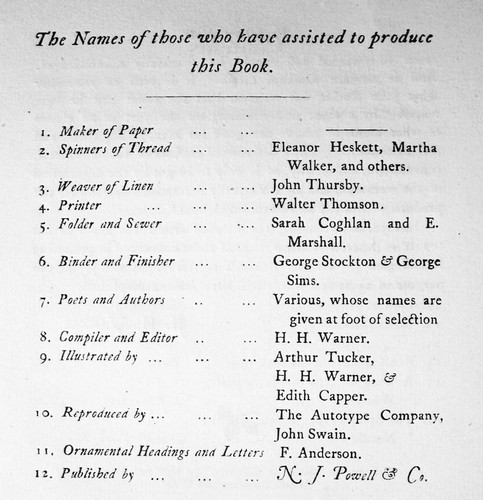

An hour’s walk would have taken Fleming from Neaum Crag to the cottage where his weavers, spinners, and paper makers worked on various parts of the handmade book. These country lanes carried him back in time to a society of familiar relations, rural traditions, forgotten skills, and blue skies. This was a world far removed from the squalor and blight of factory towns and urban slums. On a typical day in 1889, he might find Eleanor Heskett and Martha Walker spinning flax for the hand loom weaver John Thursby. The freshly woven cloth was laid out to dry on the hillside, while the paper was folded and sewn by Sarah Coghlan and E. Marshall. Eventually, Fleming assisted the book’s editor, H. H. Warner, in compiling a list of all these workers’ names and arranging for them to be inserted at the start of the book. We would not know them otherwise. Fleming and Warner intended their book to be a product of local landscape and labor, of skilled hands, mutual respect, and careful husbandry of resources. The linen cover was meant to remind the reader of the hills and grasses; it had after all been bleached “by no deleterious chemicals, but by the pure mountain air and sunshine.” It would call to mind with every turn of the page the happy manner of its production. As Warner would write in the preface, “Machine-made goods, with all their superb mechanical finish, are monotonous in their uniformity, and lack . . . human touch, interest, and individuality.” But in this case, at least, each of the 250 limited-edition copies would be unique, imperfect, and meaningful. Most books produced by steam power offered only the name of the author, publisher, and printer. Such objects did not convey the story of their creation. The same could be said of any cheaply made bowls or sheets or saucers. By contrast, when a new owner held copy #164 in her hands, she could imagine the blue-ffowered flax plants gathered from sunny fields, the nimble hands of the woman who spun the ffax into fine thread, and the furrowed brow of the weaver leaning over his loom. This is why the book was made. The moment of purchase would mean more than just an exchange of money for a commodity; it would illuminate the act of labor itself. In a time when skilled workers found themselves subordinated to the speed and efficiency of mechanical processes, Fleming’s little book reminded consumers that there was a different way to think about work and consumption. Tables, kettles, dresses, cups, and books did not have to be produced in circumstances unknown to the consumer.

figure 0.3 List of all the workers who helped make Songs of the Spindle & Legends of the Loom.

In recent years, a number of critical voices have called into question the long-term viability of our consumer habits. Affluenza, The End of the Long Summer, Eaarth, Prosperity without Growth, and Plenitude all argue the necessity of living green in the age of global warming. Forecasts of peak oil, planetary boundaries, ecological overshoot, and anthropogenic climate change challenge the ideology of exponential growth that underpins our politics and everyday life. “We’re so used to growth,” Bill McKibben observes, “that we can’t imagine its alternatives.” How can we consume without losing sight of the environment and the welfare of people in distant lands? The path forward, McKibben reckons, starts with a new vocabulary, “words that may help us think usefully about the future. Durable. Sturdy. Stable. Hardy. Robust.”

Some readers will wonder how such an ethos could gain any traction with contemporary consumers. McKibben’s vision of a simpler life may call to mind an austere and joyless existence, bereft of the myriad pleasures of modern society. All the same, it is something of a truism in the psychology of consumption that an increase in the quantity and variety of goods available to a consumer does little to increase well-being and happiness beyond a certain basic point of comfort. A long line of critics has sought to explore the vexing issue of how much might be deemed sufficient for any given person. American readers may be familiar with the works of Henry David Thoreau, Helen and Scott Nearing, Wes Jackson, Wendell Berry, and Juliet Schor. In Britain, the issue has been tackled by thinkers from John Ruskin and William Morris to E. F. Schumacher and Tim Jackson. Each of these critics has pursued different philosophical and political paths, but they all share a common commitment to an ethos of artful simplicity, what we will call in this book the culture of sufficiency.

Thomas Princen has defined sufficiency as the everyday politics and practice of steering a course between indulgence and abstinence. It is a way of life that makes use of technology and economic growth critically and selectively. Sufficiency is the choice —the “first best” choice — “to establish what is enough in everyday . . . use” of technology. This critical view of development is in turn connected to a broader understanding of the relation between human economies and the life-supporting system of the planet. For Juliet Schor, such “an environmentally aware approach to consumption” represents an awakening of the consumer to the “ecological impacts” of production and a desire to “lighten [the] footprint” of consumer spending. Clive Hamilton defines it negatively as the rejection of growth for growth’s sake. Consumers in wealthy countries have long suffered from an epidemic of “affluenza”— the psychological and sociological condition “when too much is never enough.” Robert and Edward Skidelsky argue that “economic insatiability” is a product of capitalist society. The human propensity “to compare our fortune with that of our fellows and find it wanting” has become a “commonplace of everyday life.”

Our book recovers the story of a small circle of men and women in late nineteenth-century England who tried to work out a satisfying practical alternative to mass consumption and industrial society. One hundred fifty years ago, John Ruskin and his followers tackled many of the questions we face today—with illuminating and sometimes disturbing consequences. Their concerns, like ours, arose from a sense that life was becoming less, not more, fulfilling in the age of mass consumption. They were responding to Ruskin’s prescient writings on the wealth of life and the Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century. Buying less and buying wisely, he believed, would pave the way to a healthier society and natural world. This was at once a philosophical and practical experiment, driven by central existential questions about the meaning of the good life. Acts of consumption were inseparable from choices about the public good and the environment. Should one take the train to London to buy the latest, finest linen sheets woven in a factory with power looms, or encourage the revival of hand loom weaving in a nearby village? Should one buy a new dress in the most fashionable color, or stick to clothes with locally sourced natural dyes? This critical approach to consumption brought its own share of headaches and hardships. However, the people in our story showed remarkable persistence and creativity in defending their vision, constantly experimenting with new approaches to a social problem so large and so pervasive. The fruit of their efforts was a culture of sufficiency that covered almost every aspect of life, from food and fuel, art and furniture, to science and the environment.

This quest for the simple life is arguably central to environmentalist ideology, yet few scholars have investigated its historical origins or tried to chart how people in the past attempted to practice this ethos. Most of the research on environmentalism has focused instead on love of the wilderness, strategies of conservation, or anxieties about pollution and overpopulation. The legacy of Enlightenment natural history and Romantic science from Pierre Poivre and Alexander von Humboldt to John Muir has been the subject of numerous studies. Mountain peaks, glaciers, and tropical islands offered these thinkers outdoor laboratories to test new theories of climate, geology, and ecology. Travel journals describing voyages to such spectacular places also helped popularize a quasi-religious love of wilderness. Distant mountains and forests afforded nineteenth-century travelers and readers a space for spirituality. Similar sentiments surfaced in literature and art as well. The Romantic poet William Words worth brought the full force and beauty of the natural world to the fore in The Prelude (1850). In the famous Pre-Raphaelite painting of drowned Ophelia (1851– 52), John Everett Millais’s reverence for nature appears in the painstaking representation of every single twig, leaf, and petal in the background, the figure of human mortality framed by flourishing vegetation. For these thinkers and artists, nature acquired intrinsic value beyond economic utility or older conceptions of divine design. The campaign to safeguard vast tracts of forested and mountainous regions began with this kind of revolutionary passion and spurred the foundation of the national park system in the United States and other countries. The use of prized areas was soon prohibited; even indigenous peoples were expelled. The ideal of preserving pristine territories inspired readers, artists, and scientists alike.

A second current in the scholarship on environmentalism has focused on national and local practices of conservation, or the sustainable use of land. Historians have explored preindustrial and modern traditions of resource management in forestry, soil husbandry, and fisheries. State building and geopolitical competition compelled rulers to acknowledge and tackle resource problems and ecological bottlenecks from the Venetian Republic to Tokugawa Japan. The problem of governing tropical islands seems in particular to have encouraged this sort of policy. In an island environment, ecological disturbances and resource shortages were both easier to spot and more keenly felt when overexploitation and monocultures triggered crises of production and environmental deterioration. On the island of Mauritius in the eighteenth century, the French naturalist Pierre Poivre pioneered a program of forest preserves in order to thwart a trend of desiccation and climate change, which he attributed to land clearance. Such anxieties were felt elsewhere as well in the late eighteenth century. On the much larger island of Great Britain, population growth and accelerating resource use gave rise to precocious forecasts about the physical limits to economic growth at the end of the Enlightenment. Already in 1789, the mining engineer John Williams warned that the British economy would collapse when the nation ran out of coal. Government officials and naturalists promoted policies of resource husbandry and import substitution. But such initiatives brought authorities into conflict with local communities. Early modern villages and towns struggled to maintain intricate systems of land use set up to protect common resources. In many cases, restricting the exploitation of certain areas intensified competition for the use of the remaining land. The projects of top-down sustainability thus overlapped and conflicted with a widespread system of common-use rights and local resource management.

After World War Two, the debate expanded beyond the question of preservation or conservation. A third current in the scholarship explores the emergence of environmentalism as a potent popular discourse in affluent postwar societies. Land use was no longer just a concern of local communities or national interest; environmental threats began to be conceived of at the global level. In 1948 Fairfield Osborn (Our Plundered Planet) and William Vogt (Road to Survival) warned that the ills of industrial society threatened the health of the entire biosphere. The onset of the Cold War deepened this fear of planetary apocalypse. Soon, worries about Third World overpopulation gripped American popular consciousness. In the 1968 book The Population Bomb, Anne and Paul Erlich predicted mass famine in the near future.

E. F. Schumacher questioned the notion that economies could or should grow indefinitely to accommodate burgeoning populations. He argued that a green economy aiming for limited growth offered the only long-term remedy to the problem of strained and declining resources. When the global disaster predicted by the Erlichs failed to materialize, many critics cried foul. Indeed, after 1960, the world population more than doubled and the death rate actually declined. Technological progress, it seemed, had saved the day. Mainstream economists married this faith in techno-fixes to their defense of the power of free markets. On their count, every serious type of scarcity and pollution would trigger a process of innovation and substitution.

Now, in a moment rife with irony, the quarrel between environmentalists and cornucopians (advocates of infinite economic growth) has been rekindled and transformed by the growing evidence of anthropogenic climate change. For the first time, humanity has become a geological agent, capable of reshaping the climate of the planet. Optimists minimize the danger by employing the method of discounting: future generations will be far richer than ours and therefore more capable of dealing with the problem. Another strategy of optimists is to embrace the prospect of geo-engineering. Perhaps we can cool the global climate by adding to the atmosphere new aerosols to counter the greenhouse effect. However, the broader effects of such intervention remain very much in doubt. As Clive Hamilton has shown, scientists are proposing to spray the atmosphere with heat-deflecting sulfur particles, or to stimulate massive algal blooms to suck carbon out of the air, even though no one can say with certainty what the repercussions might be. In general, ecological systems tend to be more complex than we like to imagine, and deleterious unintended consequences all too common. Therefore, the failure to reduce our emissions now could well lead to the crisis spinning out of control. At the same time, the task of transforming the system is nightmarishly complex. If economic growth drives emissions, should we not cut growth to cut emissions? How do we restructure the energy base of our economy without challenging the consumer orientation of our civilization?

This is where Ruskin and his followers claim our attention. Earlier than most critics, they sought a way to exit the fossil fuel economy and consumer society. In a letter from October 1877, Ruskin advised a concerned businessman on how to live a better life. He wrote:

First. Keep a working man’s dress at the office, and always walk home and return in it; so as to be able to put your hand to anything that is useful. Instead of the fashionable vanities of competitive gymnastics, learn common forge work, and to plane and saw well;— then if you find in the city you live in, that everything which human hands and arms are able [to do] . . . is done by machinery,— you will come clearly to understand . . . that . . . to dig coal out of pits to drive dead steam-engines, is an absurdity, waste, and wickedness.

Those who sought a simpler life were to stay active, eschew the encumbrances of fashion, learn physical skills that might be useful, make things by hand, and question the benefits of relying on machine power and the labor of others. Ruskin’s message is infused with an ideal of sufficiency quite close in spirit to “maker” fairs and DIY projects. His disgust with coal is not so far removed from our own reaction to news of vanishing glaciers and plastic debris in the ocean. Long before Silent Spring and Earth Day, middle-class people worried that consumer society was destroying the natural world.

Though Ruskin’s vision has obvious affinities with modern environmentalism, the precise role of his political economy in the making of green ideology has not yet been fully investigated. Some scholars have understood his work to be derivative of William Words worth’s Romantic vision of beauty and nature. Both men lived in the Lake District, separated by roughly a generation, and both were enamored with the area’s mountains and lakes. Yet too much insistence on continuity will obscure the original vision of Ruskin, which linked beauty and work with ethical consumption. Many scholars have commented on Ruskin’s disturbing vision of the slum-ridden, money-obsessed Victorian metropolis, but they have usually left aside his understanding of how these markets exploited the environment. Ruskin does receive credit as an early preservationist for his battle against the expansion of the railways in the Lake District, although it is hard for us to escape the verdict that he was fighting the wrong enemy, given that mass transit eventually came to be considered ecologically more sound than automobile travel. Ruskin’s place in the history of environmentalism can be seen in other ways too, for instance in his influence on important activists like Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley. In the 1870s, a controversy erupted regarding the construction of a water pipeline and aqueduct between rural Cumbria and the burgeoning city of Manchester. Rawnsley and Ruskin both opposed the damming of Lake Thirlmere. The debate filled the newspapers for months and proved a seminal moment for the environmentalist lobby in Britain, rehearsing a strategy of nature conservancy that would be employed frequently in decades to come. Rawnsley also spearheaded a movement to found the National Trust, an organization dedicated to the preservation of traditional landscapes and architecture in Britain. Rawnsley’s National Trust activities and other projects promoted more than just the protection of land; he also wanted to revive and preserve the skills and customs of the common people. Thus Rawnsley and his wife organized local artisan workshops and helped create a market for their products.

figure 0.4 John Ruskin, ca. 1885. Courtesy of the Brantwood Trust.

What has received a great deal of attention is Ruskin’s apocalyptic theology, notably his lament for the spiritual decline of England, its pursuit of mammon, and its brutal alteration of the God-given natural world. These anxieties have been characterized narrowly as the effect of brooding religiosity or declining mental health. It is indeed difficult —as it was for Ruskin’s own peers—to disregard his periodic hallucinations, fevers, and depression. Yet too great an emphasis on the apocalypse or madness will distort Ruskin’s lasting intellectual contribution, for his most important writings, from Unto This Last (1860) to Fors Clavigera (1871– 84), present a powerful indictment of consumer society’s mismanagement of resources. Ruskin became the first great intellectual figure to broach the idea that coal burning gave rise to anthropogenic climate change. This culminated in his 1884 lectures on the Storm Cloud, a bleak vision of planetary degradation. These letters and lectures are discussed at length in chapter 1. Despite the mystical language and obscure symbolism used to convey his sense of moral and physical peril, Ruskin’s observations are undeniably astute and unnerving to read. His anxieties about atmospheric pollution eerily foreshadow the dark tenor of environmentalism in the postwar era.

Another way to gauge Ruskin’s significance, and account for his undeserved neglect, is to compare him directly to his near contemporary John Muir—the iconic figure of American preservationism. Muir (1838–1914) and Ruskin (1819–1900) shared a Scottish mercantile and Presbyterian background. Both men received an education steeped in Enlightenment natural history and Romantic science, including the writings of Alexander von Humboldt. They traveled widely and loved mountain landscapes, in Muir’s case Alaska and the Sierra Nevada range of California, and for Ruskin the Lake District and Switzerland. Both developed a strong fascination with glaciers, to the point of engaging actively in contemporary controversies over glacial science. In middle age, each man settled on a large piece of property, Muir on the Strentzel ranch outside San Francisco, Ruskin at Brantwood near Coniston. They were both keen to shape public opinion on social and environmental issues, though Ruskin shied away from direct engagement with politicians. What separated them was a philosophical difference on the meaning of natural beauty.

Ruskin was by training and inclination steeped in the fine arts, classical learning, and the history of landscape painting. The artistic representations of nature with which he was most familiar included pastoral scenes with shepherds or mythological beings, gentle lakes and hills. At the same time, he championed the work of J. M. W. Turner, whose innovative landscapes often depicted the fiercer, more spectacular elements of nature. But Ruskin tended to appreciate Turner’s understanding of the human element in the midst of nature—the smoke-filled urban scenes, the train roaring through its own steam, a barely visible mast engulfed by a roiling ocean. Ruskin memorably praised Turner’s painting The Slave Ship (1840), in which a frightening storm at sea takes up a majority of the canvas. Yet the sea is not the only subject; instead, the tiny ship with its ill-fated passengers suggests an anthropocentric slant. Ruskin wrote that the ship was “guilty” and “girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror.” The storm’s ferocity was filtered through the human gaze.

John Muir’s experience of Half Dome in Yosemite National Park in 1875 could not have been more different. To his mind humans added nothing of worth to the mountain. In fact, human influence would taint its majesty —if only temporarily. He lamented the failure to keep Half Dome cordoned off from hikers: “Now the pines will be carved with the initials of Smith and Jones, and the gardens strewn with tin cans and bottles.” But he took solace in the mountain’s power to slough off any human debris: “the winter gales will blow most of this rubbish away, and avalanches may strip off the ladders . . . When a mountain is climbed it is said to be conquered — as well say a man is conquered when a fly lights on his head.” He continued, “Tissiack will hardly be more conquered, now that man is added to her list of visitors. His louder scream and heavier scrambling will not stir a line of her countenance.” In Muir’s world, nature was the most wondrous when human influence was removed, whereas Ruskin was never quite at ease with the idea of pure, uninhabited wilderness.

A passage from The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) illuminates Ruskin’s aversion to an unpeopled natural world still more, while clarifying what he felt humans brought to nature. He recounted a walk in the forest among the subalpine mountains of Jura: “[C]lear green streams” crossed the valley in a bed of oxalis and wood anemone, with a hawk sailing in the sky high above the long-inhabited foothills. It was a scene of “secluded and serious beauty.” Then a strange thought suddenly cast a “blankness and chill” over the landscape. He imagined that it was a “scene in some aboriginal forest of the New Continent.” In an instant, the lovely forest transformed itself from a blissfully secluded idyll to a never-peopled world, a natural order devoid of human influence. Such a place could hold for Ruskin none of the beauty of tamed woodland “dyed by the deep colours of human endurance, valour, and virtue.” He pulled himself back from the unnerving reverie, reminded that on this horizon, thankfully, were familiar marks of civilization and architecture— “the iron walls of Joux, and the four-square keep of Granson.” For Ruskin, only through human memory and art did the wilderness shed its alien countenance and gain meaning and value. It was the “union of story and scenery,” the ability of humans to weave their own narrative through the forests and mountains and plains, which created beauty, not nature in its own right. To Muir, this was a mistaken view. All of nature was sacred and marvelous, whether touched by humans or not. Such “holiness” reached its highest pitch among the lofty peaks rather than the lowlands, along a vast and barren cliff face rather than a well-worn foot path. Muir wrote to Ralph Waldo Emerson: “I do not beckon you because mountains are more glorious than plains, but because they are less glorious, because they are simple & absorbable. Here we may most easily see God.” At the heart of Muir’s preservationism, then, lay the alien presence that sent chills down Ruskin’s spine.

figure 0.5 The Old Man of Coniston seen from the Brantwood lawn, 2011.

While there is much to admire in Muir’s conception of nature, it glossed over the mundane realities of human existence: agriculture, shelter, work, and population. This contrast, more than any other reason, may explain why Ruskin has been neglected by historians and scholars of environmentalism. For those who place the cult of the wilderness at the center of environmentalist thought, Ruskin is, no doubt, like Emerson, too much a denizen of the lowlands, too much concerned with human welfare and common activities. But we might just as well turn the criticism on its head. In the age of anthropogenic climate change, environmentalist thought has to deal first and foremost with the problem of consumer demand and carbon emissions. And here, Ruskin may be of greater relevance than Muir. Ruskin believed the way to a more fulfilling life required a critique of classical political economy; the laws of supply and demand had to be seen within a far more expansive framework that included foresight regarding the use of natural resources. At the heart of this critique was an ethics of consumption—summed up by the famous dictum “There is no wealth but life.” In Ruskin’s view, the landscapes of the Jura and the Lake District were shrouded in beauty and poetry. But the fate of the natural world depended on the place of ethics in the economy. For every purchase might support another factory, another lost forest, another smokestack.

Copyright notice: An excerpt from Green Victorians: The Simple Life in John Ruskin's Lake District by Vicky Albritton and Fredrik Albritton Jonsson, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2016 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)