Hilma af Klint

A Biography

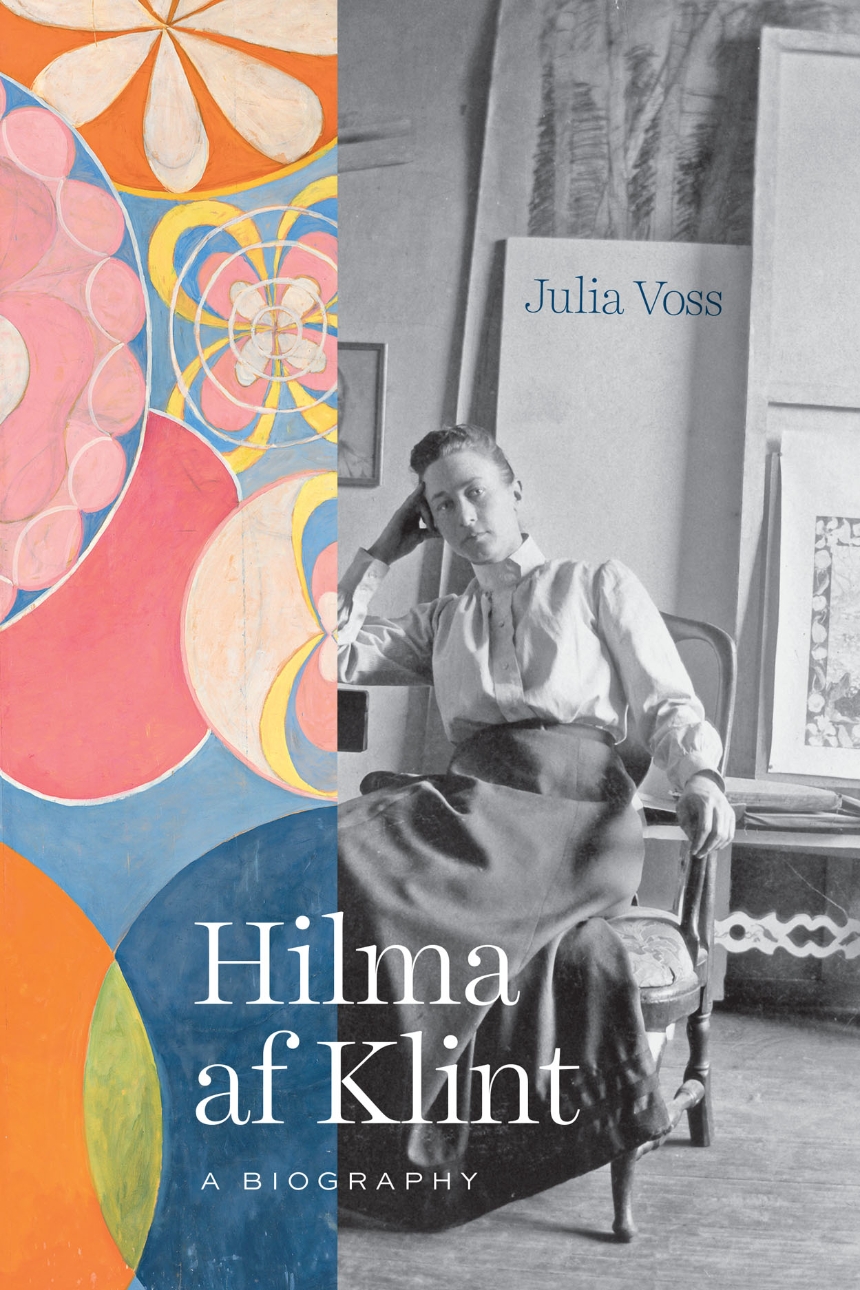

The Swedish painter Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was forty-four years old when she broke with the academic tradition in which she had been trained to produce a body of radical, abstract works the likes of which had never been seen before. Today, it is widely accepted that af Klint was one of the earliest abstract academic painters in Europe.

But this is only part of her story. Not only was she a working female artist, she was also an avowed clairvoyant and mystic. Like many of the artists at the turn of the twentieth century who developed some version of abstract painting, af Klint studied Theosophy, which holds that science, art, and religion are all reflections of an underlying life-form that can be harnessed through meditation, study, and experimentation. Well before Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich declared themselves the inventors of abstraction, af Klint was working in a nonrepresentational mode, producing a powerful visual language that continues to speak to audiences today. The exhibition of her work in 2018 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City attracted more than 600,000 visitors, making it the most-attended show in the history of the institution.

Despite her enormous popularity, there has not yet been a biography of af Klint—until now. Inspired by her first encounter with the artist’s work in 2008, Julia Voss set out to learn Swedish and research af Klint’s life—not only who the artist was but what drove and inspired her. The result is a fascinating biography of an artist who is as great as she is enigmatic.

424 pages | 44 color plates, 49 halftones | 6 x 9 | © 2022

Reviews

Table of Contents

Chronology

Introduction

Part I. Family, Childhood, and Youth in Stockholm

1. Mary Wollstonecraft Visits Sweden and Is Upset

2. Birth

3. School and Religion

4. An Exhibition in London

5. Bertha Valerius and the Dead

6. Kerstin Cardon’s Painting School

7. Hermina’s Death

Part II. Study at the Academy and Independent Work

1. The Academy

2. Guardian Spirit

3. The Prize

4. Anna Cassel

5. “My First Experience with Mediumship”

6. The Young Artist

7. Dr. Helleday and Love

8. The Five

9. Art from the Orient

10. Rose and Cross

11. At the Veterinary Institute

12. Children’s Books and Decorative Art

13. Italy

14. Genius

Part III. Paintings for the Temple

1. Old Images

2. Revolution

3. Primordial Chaos

4. Eros

5. Medium

6. The Ten Largest

7. “I Was the Instrument of Ecstasy”

8. Rudolf Steiner Visits Sweden

9. The Young Ones

10. Sigrid Lancén

11. The Association of Swedish Women Artists

12. Frank Heyman

13. Island Kingdom in Mälaren

14. First Exhibition with the Theosophists

15. Tree of Knowledge

16. The Kiss

17. Singoalla

18. The Baltic Exhibition

19. War

20. Saint George

21. Kandinsky in Stockholm

22. Parsifal and Atom

23. The Studio on Munsö

24. Thomasine Anderson

Part IV. Dornach, Amsterdam, and London

1. The Suitcase Museum

2. Flowers, Mosses, and Lichens

3. First Visit to the Goetheanum

4. “Belongs to the Astral World According to Doctor Steiner”

5. The Fire and the Letter

6. Amsterdam

7. London

Part V. Temple and Later Years

1. The Temple and the Spiral

2. +x

3. A Temple in New York

4. The London Blitz

5. Future Woman

6. National Socialism

7. Lecture in Stockholm

8. “Degenerate” Art in Germany and Abstract Art in New York

9. Tyra Kleen and the Plan for a Museum

10 Last Months

11. Conclusion

Afterword by Johan af Klint

Afterword by Ulrika af Klint

Appendix 1. Hilma af Klint’s Travels and Places of Residence

Appendix 2. The Library of Hilma af Klint

Acknowledgments

Illustration Sources

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Excerpt

Around the age of seventy, Hilma af Klint began to separate the documents and artworks she would preserve from those she would destroy. In this she was no different from many artists, but in other ways she was, and she knew it. Af Klint was not just an artist. She was also a mystic who said that her most powerful, abstract works were painted under the direction of higher spirits communicating from the astral plane. Since the late nineteenth century, an array of spiritualist teachings had been revolutionizing religious understanding the world over. For example, Theosophy, among the most popular, sought to reconcile the spirit with the natural and scientific worlds, and many artists embraced it: Kandinsky, Mondrian, Kupka, and Arthur Dove all studied Theosophy; none of them, however, ever publicly suggested their canvases were the expressions of any consciousness other than their own. Realizing the world was not yet ready for what she had created and what motivated it, in 1932 af Klint wrote that none of her paintings or drawings should be shown until twenty years after her death.

Thus she catapulted her life’s work into the future, out of the first half of the twentieth century into the second, safe from the judgment of her contemporaries. They were not to have the last word.

Who was this woman who sent her work to the future in a time capsule, putting her faith in generations to come? When she died, af Klint left behind more than 26,000 pages of text and 1,300 paintings, a formidable legacy. One can see from this material how, over and over again, she broke every rule society set for her—as an art student at the Royal Academy in Stockholm, as a woman at the turn of the twentieth century, and as a modern artist. It is widely accepted now that well before painters like Wassily Kandinsky or Kazimir Malevich claimed to have invented abstraction, she had been painting in that mode for several years—first in small formats and then on an enormous scale. When she began to paint this way, she was forty-four years old. It was November 1906. “The experiments I have undertaken,” she wrote as she set off on this new path, “will astound humanity.”

Any memory of these works faded after she died, and it took decades to bring them back to light. Why so long? The fact is that profound changes in the fine arts often meet with vehement rejection, and the resistance to af Klint’s reappraisal was evident the first time her work was presented to a wide audience. In 1986, more than forty years after her death, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art organized an exhibition titled The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890–1985, which offered a new perspective on the history of nonrepresentational art. In the catalogue and exhibition, a relationship was suggested between abstraction and the various spiritual movements that spread through the Western world around the turn of the twentieth century. It was a major show, and landmark works of abstraction were loaned by museums in Munich, Paris, Moscow, and New York.

Af Klint’s paintings came crashing into this venerable canon like a meteor. Suddenly her huge canvases were hanging next to those of recognized modernist masters. The unknown Swedish woman seemed to come out of nowhere, and the reception was largely negative. The American critic Hilton Kramer wrote: “Hilma af Klint’s paintings are essentially colored diagrams. To accord them a place of honor alongside the work of Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich, and Kupka . . . is absurd. Af Klint is simply not an artist in their class and—dare one say it?—would never have been given this inflated treatment if she had not been a woman.” Kramer wasn’t the only person who thought so. Silence fell again on the subject of Hilma af Klint.

It took two more decades before the Moderna Museet in Stockholm mounted a large-scale offensive meant to secure a place for af Klint in the modernist canon. In 2013 the institution sponsored Pioneer of Abstraction, the largest exhibition of her work to that point, and sent the show on tour through Europe. Excitement began to gather around the artist, and yet again the paintings met with resistance. The objections were phrased more carefully this time, but they came from prominent quarters. Curator Leah Dickerman of the Museum of Modern Art in New York wrote: “[Af Klint] painted in isolation and did not exhibit her works, nor did she participate in public discussions of that time. I find what she did absolutely fascinating, but am not even sure she saw her paintings as art works.” It took a third try for the story to take a new turn. The 2018 show at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, broke all attendance records, attracting more than 600,000 visitors—more than any exhibition since the museum’s founding. The catalogue became a best seller. The New York Times ran a piece called “Hilma Who? No More!” Since October 2019, the Guggenheim has continued to show several of her paintings. The art history outsider has become a star.